Introduction

Enhancing sprint performance is a fundamental training goal across a wide range of sports and disciplines. For any athlete, improvements in overall performance are often associated with increases in acceleration capacity and/or maximal sprint speed (MSS) [1], which are usually assessed through standard measures such as 10-metre sprint time (early acceleration phase), 30-metre sprint time (combined acceleration and transition phases), and top-speed, all of which are highly relevant to athletic performance [2]. These gains, however, are typically marginal (often measurable in only a few milliseconds) and may take years to be achieved, particularly in elite athletes [2, 3].

In contrast, younger or less experienced athletes tend to exhibit faster improvements, in line with the principle of diminishing returns [4, 5], whereas highly trained athletes commonly show smaller, slower, and more specific adaptations. Given its critical relevance to success in both individual and team sports, sprint development remains a central focus of well-structured training programmes.

To advance current practices, it is essential to understand better the distinct adaptation rates and progression patterns associated with speed development across different populations, including various sports, age groups, and competitive levels [5–7]. Such knowledge can inform the design of more effective and individualised sprint training interventions, ultimately enhancing performance and minimising the risk of suboptimal outcomes. Therefore, this perspective article aims to highlight the need for a more comprehensive and context-specific analysis of sprint development, emphasising the importance of aligning training approaches with individual athlete profiles, sport-specific demands, and methodological considerations such as study design differences and intervention characteristics (e.g., training load, training duration, and frequency) that may directly influence sprint-related outcomes [8], with a particular focus on the implementation of unresisted and resisted sprint training methods (i.e., UST and RST, respectively).

Why is it essential to consistently prescribe speed training for athletes, regardless of their sport, competitive level, age, or gender?

Speed development should be prioritised across a range of athletic populations due to its widespread relevance and decisive role in multiple sports [9, 10]. For instance, Oliva-Lozano et al. [11] reported that professional soccer players are sometimes required to perform maximal-intensity sprints longer than 30 m, reaching velocities of approximately 30 km/h. Similarly, in sports such as rugby union, rugby league, American football (National Football League, NFL), and field hockey, MSS has been consistently associated with performance [12]. However, its relative importance differs across contexts: in track sprint events, MSS is a primary determinant of performance outcomes [3, 13]. Meanwhile, MSS functions more as a secondary determinant in team sports (e.g., soccer, rugby, and field hockey), complementing other crucial qualities, such as acceleration ability, repeated-sprint capacity, and technical-tactical skills [12, 14–16]. This reinforces the notion that MSS-oriented training should be integrated into virtually all strength and conditioning programmes. Consequently, coaches must consider the distinct phases of sprinting, namely, acceleration, transition, and top speed, and develop the ability to accelerate effectively and sustain MSS over extended distances when designing and prescribing sprint training programmes [12].

Sprint phases are typically delineated based on changes in step kinematics and variation in speed profiles (e.g., acceleration from 0 to ≈ 30 m, transition until the point of speed stabilisation, and top speed once MSS is reached) [17, 18]. MSS itself is usually assessed using timing gates (TGs), radar guns, or highspeed videos, which allow practitioners to accurately determine the maximal speed attained during a sprint effort [2, 19]. Both acceleration and MSS are regularly monitored and considered relevant indicators of sprint-specific actions performed during both training and competition [1, 9, 12]. To elicit the necessary adaptations required for elite athletes, it is essential to follow and adhere to the principle of training specificity [12, 20], which also includes selecting appropriate drills and stimuli that are able to reflect the actual needs and demands of traditional sprint efforts [12, 20]. As such, the correct identification of the physiological and mechanical determinants of sprint speed is fundamental not only for accurately profiling athletes but also for translating this knowledge into concrete methodological decisions, such as tailoring exercise programming (e.g., UST vs. RST, adequate load prescription, and individualised sprint distance), as well as adjusting training intensity and monitoring training-induced adaptations [12, 20, 21].

Highlighting the importance of sprint assessment

The ability to track changes over time is a crucial aspect of athlete testing, regardless of the physical quality assessed. In light of the aforementioned difficulty in reducing sprint times (i.e., improving sprint speed) by just a few milliseconds, which may require years of hard, dedicated training [22, 23], the assessment methods, their specific parameters, and standardised protocols are paramount to ensuring the precision and consistency of these measurements. Among numerous factors, potential confounding variables must be identified and minimised as much as possible, especially when trying to understand and accurately isolate the training effects on speed-related qualities [12]. From a practical standpoint, this means that, for example, if we want to perform a 30-metre sprint test using TGs, several aspects require careful consideration. Imagine a coach who, during a pre-test, places the TG one metre behind the 0-metre line, with an athlete positioned in a two-point stance, and eight weeks later, during a post-test, places the TG 0.5 m behind the line and does not control foot positioning or trunk-related countermovement actions. This will result in slower times compared to the pre-test; however, this outcome is not a true training effect, but rather the result of uncontrolled confounding variables during the sprint speed test. Notably, it is of utmost importance to consider changes in body mass (BM) (and body composition) when trying to understand these training effects, especially in collision sports such as rugby union and American football [24, 25]. Indeed, sprint momentum (SM) must be considered a relevant and complementary indicator of sport-specific performance [16].

Another important aspect to consider in sprint speed assessments is the use of appropriate technology to evaluate elite athletes [2]. Considering logistical and financial constraints, TGs are generally preferable to mobile apps, since other gold-standard equipment (i.e., radar and laser systems or high-speed cameras) may be prohibitively expensive for most practitioners. For example, when testing a large number of athletes (e.g., more than 20–30), mobile apps may require considerable time and operational effort, in addition to the need for state-of-the-art smartphones, which are often associated with substantial financial costs due to their advanced sensors and high-resolution cameras. In contrast, four pairs of TGs (e.g., Chronojump, Bos-cosystem; €1,400) can provide reliable and consistent data for monitoring changes over time. Other equipment (radar, laser, motorised resistance devices, or highspeed cameras) remains financially unfeasible for most coaches, with costs ranging from approximately €2,500 to over €10,000. When dealing with large groups of athletes (e.g., ≈ 40–50 athletes), as commonly occurs in high-volume testing settings, affordable and efficient tools such as jump mats and TGs become crucial to ensure rapid and accurate assessments.

Once coaches have decided which equipment best suits their needs and is accessible in terms of cost and practicality, defining the type of information that can be extracted from the technology becomes critical. Essentially, TGs measure sprint times, with most systems including post-processing software that filters out double contacts. If coaches have, for example, four pairs of TGs, the selection of split distances depends on the specific performance variables being assessed [26].

Table 1

Key considerations for assessing sprint speed with timing gates

For acceleration capacity, TGs can be positioned at 0–5 m and 5–10 m, with the remaining two pairs at 10–20 m and 20–30 m. Conversely, precisely estimating MSS involves using recommended placements of 0–10 m, 10–20 m, 20–25 m, and 25–30 m. These setup recommendations are based on the observation that, in team sports, athletes reach approximately 95% of their MSS within a 20-metre sprint from a standing start, although a longer distance is required to reach their top speed [26, 27]. Accordingly, shorter split distances (i.e., 5 m) have been previously recommended to estimate MSS more accurately than 10-metre split times when compared to radar-based measurements [26]. Table 1 summarises additional methodological details and contextual considerations for accurately assessing sprint speed with TGs.

Sprint training methods

Before describing the methods used to improve sprint performance, it is necessary to clarify the rationale and contextual factors underlying their application. To maximise positive adaptations, sprint speed should be trained outside the competitive environment using methods that allow for more precise control of training variables, in a non-fatigued state [12]. These conditions can be easily monitored with practical tools, such as ratings of perceived exertion, which help confirm that athletes are sufficiently recovered before and during sprint training sessions [28, 29]. As a complement, sprint capacity can be developed through a variety of pre-planned training scenarios, including technical, tactical, or strategic ones, while accounting for the inherent unpredictability of sport-specific contexts [30]. Such unpredictability is often conceptualised within the control-chaos continuum, as reported elsewhere [31]. In this regard, developing sprint speed is essential, not only to meet the physical demands of the sport but also because it is consistently recognised as a key determinant of athletic performance [32] and a relevant criterion for selection across various sports [27, 33].

Sprint training methods are generally classified as primary (i.e., unresisted or traditional sprint efforts), secondary (i.e., assisted or resisted sprints), and tertiary (i.e., plyometrics, strength-power training, and heavy sled-towing) [12, 32] (see the complete definition of these training methods in Table 2). While unresisted sprinting should remain a fundamental component of sprint training throughout the season, the inclusion of secondary and tertiary methods is also recommended as part of a structured and well-organised speed development programme. Among these methods, resisted sprinting has traditionally been used to enhance acceleration capacity and MSS by practitioners within distinct individual and team sport disciplines [34]. Several implements are commonly used under resisted sprinting conditions, which involve the athlete running with an additional load, such as a loaded sled, weighted-vest (WV), parachute, or sand surface [12, 32]. Recently, the use of sled-towing (ST) and WV as training tools to enhance acceleration and MSS has garnered considerable attention from researchers, coaches, and practitioners [12, 35]. However, evidence regarding their effectiveness in developing these key capacities remains debatable and inconclusive [1, 9, 12]. Therefore, further research is needed to clarify and elucidate the short- and long-term effects of these sprint training strategies in athletes with diverse training needs and backgrounds.

Table 2

Summary of commonly used methods to improve sprint performance and their respective implements

[i] Adapted and modified from Zabaloy et al. [11].

Current evidence on the short- and long-term effects of resisted sprinting using sled-towing and weighted vests

Resisted sprinting using ST and WV is a widely discussed topic and will likely continue to be a focus of interest for years to come. While the acute and shortterm effects are relatively well understood, the findings from experimental studies lasting up to eight weeks remain less conclusive and are often subject to controversy. One of the main points of debate concerns the specific ranges of external loads that should be applied during ST or WV training to elicit meaningful adaptations (i.e., a test score variation that exceeds the expected measurement error and the natural variability of the athlete) [36] in the different phases of sprinting. To date, the concept of an “optimal” load is still inconclusive. Nonetheless, it is generally accepted that the loading scheme should be tailored to the specific demands of the sport and sprint distance. From an applied perspective, the resistance (i.e., external loads) should be prescribed to enhance the strength-power qualities and intermuscular coordination in the primary muscle groups involved in traditional unresisted sprinting, while providing an effective training stimulus without substantially altering sprint mechanics [9, 12]. The following sub-sections summarise key research findings that should be considered by coaches and sport scientists when designing RST programmes. For the sake of clarity, the short- and long-term effects are categorised into the following domains: force-power production, sprint kinematics, metabolic responses, neuromuscular adaptations (including neural and electromyographic data), leg stiffness, and muscle architecture.

Short-term effects of increasing sled and vest loads

One important aspect to consider is that decreases in sprint speed are both load- and distance-dependent. In real-world scenarios, this implies that the greater the load applied during ST or WV sprinting, the shorter the distance typically adopted in sprint bouts [37]. This principle provides a theoretical foundation for the systematic planning and organisation of RST interventions designed to promote sprint-specific adaptations [12]. Several short-term changes have been reported in the scientific literature, regardless of the sport, competitive level, age category, or sex [12, 38–40].

As a theoretical premise, it is crucial to distinguish between ST and WV when applied to sprinting, as each method imposes distinct mechanical and physiological demands and generates divergent responses in athletes with different training backgrounds [12, 41, 42]. It is also important to note that when using WV, applying heavy loads [e.g., > 30% velocity decrement (Vdec)] appears impractical due to factors such as load placement, vest capacity, safety concerns, and other logistical limitations (e.g., limited load capacities). For a more comprehensive understanding of these highly specific aspects, readers are encouraged to consult previous studies conducted on this topic [12, 35, 41, 42]. For practical purposes, the main insights and findings derived from these studies are summarised below:

– With WV, the added resistance results from the weight of the device and acts vertically downward.

– With ST, the sled load is positioned behind the athlete, and the resulting resistance force is directed slightly downward and backwards due to the lower attachment point on the sled relative to the athlete’s body. Variations may also occur depending on whether the sled is connected via a waist belt or shoulder harness [43].

– ST may be more effective for enhancing the early acceleration phase, as it more closely replicates the biomechanical demands of the task, such as increased trunk lean and greater horizontal force production during the stance phase.

– WV has been shown to exert less influence on trunk angle (i.e., athletes tend to remain more upright). During the later stages of acceleration and at top speed, when braking forces become more relevant, WV provides a greater eccentric braking load at the beginning of the stance phase.

– Notably, regardless of the loading condition, maximum power during WV sprints tends to peak at approximately one second, whereas the highest power output in soccer players has been observed during unresisted sprinting [42].

– Given the distinct effects and mechanical characteristics of each method, coaches should consider not only the type of resistance and the load range used, but also the specific adaptations and acute responses that each method may produce. WV offers greater versatility, allowing for a variety of sprint drills, including directional changes, curvilinear sprints, and decelerations, that are often as relevant as linear sprinting in many sports.

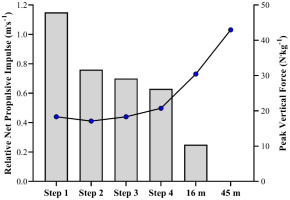

The greater the applied load, the greater the resulting impulse (i.e., increased force output and time of application), leading to longer ground contact times, shorter flight times, and a concomitant reduction in sprint speed [1, 37, 40]. While horizontal force production and relative net horizontal propulsive impulse are essential during the initial steps of sprinting (i.e., the early acceleration phase), vertical (and resultant) forces become increasingly critical for attaining higher speeds [12, 35, 44, 45] (Figure 1). Indeed, applying greater forces against gravity increases a runner’s vertical velocity at takeoff, thereby extending flight time and the distance covered between successive steps [44].

Thus, in practical terms, since team-sport athletes (e.g., soccer players) very rarely initiate sprinting actions from static positions, or even from very low speeds [31], what is the central objective of using heavy or very heavy sled loads (i.e., ≥ 50% BM or ≥ 30% Vdec) in their RST programmes? A previous study involving nationalteam rugby players from different playing positions reported that progressively increasing sled loads (i.e., unresisted, 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% BM) led to a gradual disruption in sprinting technique over both short (5 m) and longer (20 m) distances [37]. This disruption was marked by a substantial increase in hip flexion, contrasting with the sprint-specific mechanics commonly observed in most sports, where maximal sprint efforts commonly begin at low-to-moderate speeds and the trunk tends to adopt a more upright (i.e., vertically oriented) position [37, 38]. Additionally, while ST with heavy or very heavy loads (i.e., ≥ 50% BM or > 30% Vdec) unquestionably increases theoretical maximal force (F0) [46], the heavy RST approach is also associated with a substantial reduction in MSS [37, 40, 47], which even compromises the use of the term “sprint” in its nomenclature [37]. For example, sled loads of 60% and 80% BM have been shown to reduce 5-metre sprint speed by approximately 35% and 47%, and 20-metre speed by 46% and 68%, respectively, in elite male rugby players [37]. In other words, with a nearly 70% reduction in MSS over 20 m, athletes are running at a low-to-moderate pace rather than approaching their MSS.

Figure 1

Relative net horizontal propulsive impulse (bars) and peak vertical force output (line) from steps 1–4, and at the 16 and 45 m marks of a sprint effort. Adapted and reproduced from: Wild et al. [45]

From a kinematic perspective, the variables traditionally assessed in sprint efforts include contact time, stride length and frequency, flight time, contact distance, trunk angle, and joint angular kinematics. Current evidence clearly indicates that increasing loads affect these variables in different ways. For example, as previously mentioned, increasing the load during ST leads to a greater contact time and trunk inclination, while stride length and flight time decrease, ultimately contributing to a reduction in sprint speed across a wide range of distances [37, 40]. Moreover, alterations in joint angular kinematics at the hip, knee, and ankle were observed in elite rugby players [37] when sprinting under different loading conditions. The effects of additional external loading during sprinting with a WV on step frequency and step length may, in fact, explain the observed decrements in speed. Simultaneously, the added load increases ground contact time and decreases flight time during the gait cycle [42, 48].

When deciding which loads to apply to ST or WV sessions, have coaches ever thought about the metabolic demands induced by these loads? This is a critical aspect to consider, as many team sports frequently train concurrently, resulting in relatively short time periods to recover from one part of training (e.g., sprint training sessions) to the next one (e.g., sport-specific training sessions). For example, one study showed that heavier loads acutely induced greater performance impairments and metabolic responses compared to lighter loads. However, all loading conditions (i.e., from 20% to 80% BM) led to a complete (or at least partial) recovery of sprint capacity after 24 hours of rest [12, 38, 40]. Another interesting study by Monahan et al. [47] revealed that loads of approximately 22% Vdec increased metabolism (i.e., blood lactate), heart rate, and subjective perception of effort when compared to a load of approximately 7% Vdec. In brief, heavier sled loads increase internal and external demands during RST and, consequently, both acute and chronic fatigue [12, 38, 40]. Consistent with these metabolic and physiological effects, two applied studies in elite cohorts revealed clear barriers to implementing very heavy sled loads (i.e., ≈ 80% BM [49]) in practice. In national-team rugby, players and coaching staff reported excessive neuromuscular fatigue and a transient performance decrement that prevented effective training the next day; in professional soccer, the 80% BM protocol lasted only two weeks before being discontinued at the staff’s request due to cumulative fatigue during and after RST sessions (i.e., personal communication; study conducted with a first-division soccer team).

In contrast, switching to 20% BM for the subsequent six weeks proceeded without issues. Collectively, these observations reinforce that such very heavy sled loads are highly problematic and should not be recommended in high-performance sport settings [12, 37, 40]. Therefore, practitioners must consider their impact on other concurrent forms of training, competitive performance, and the overall training load, bearing in mind that excessive (and non-specific) loads will almost certainly impair subsequent activities, especially within the 24–48 hour recovery period [12, 38, 40].

Neither muscle architecture nor neural adaptations (short- and long-term changes) to UST and RST with ST or WV have been thoroughly investigated. Nevertheless, little is currently known regarding the latter factors. We should consider, however, that force production during a complex movement (e.g., maximal sprinting) requires the synchronised recruitment of several muscle groups across multiple joints. Hence, the magnitude of force output depends on various factors, including the mass and cross-sectional area of agonistic and synergistic muscles, the extent to which the nervous system can activate these muscles, and the ability to coordinate their activation during the movement task [12]. Conversely, neuromuscular activity during sprinting under different loading conditions has been recently investigated [39, 40], with similar findings reported for amateur male rugby players and highly trained male and female sprinters. Collectively, both studies demonstrated that external loads altered the electromyographic activity of the biceps femoris long head (reduced activation) and rectus femoris (increased activation), with these acute neuromuscular changes concurrently influencing sprint kinematics. These alterations became more evident with heavy loads, raising further questions and concerns regarding the advantages of applying heavier loads over moderate or lighter loading conditions during RST [39, 40, 47].

Regarding leg stiffness, Lorimer et al. [50] indicated that it provides a valuable measure for assessing the influence of kinetics and kinematics on tissues during running. Likewise, this variable is significant when aiming to improve top speed performance [51]. It is important to note that lower values of leg stiffness have been associated with fatigue [52] and with inefficient absorption and storage of elastic energy during the stretch-shortening cycle [53]. Overall, the acute effects observed in amateur rugby players [40] suggest that ST loads have a drastic impact on leg stiffness, with the most pronounced differences occurring at 50% Vdec loads during top-speed phases. A stiffer system is likely to have positive implications for running, such as an increased rate of force development (RFD) at ground contact, resulting in reduced contact time and higher peak force [54]. In fact, the reflexive control of musculotendinous stiffness plays a crucial role in sprint performance, whereas fatigue at the neuromuscular junction may hinder full muscle activation during sprinting [12, 54].

In this regard, coaches should consider that training with heavy loads may interfere with an athlete’s ability to produce force within very short time frames (i.e., RFD), and consequently impair their capacity to generate acceleration, speed, and power during these critical moments [55]. Following this assumption, and in line with the previously observed acute-delayed effects of different loading schemes, the key points outlined below should be considered essential for the appropriate selection of loads when prescribing RST programmes [55]:

– A motor unit is trained in direct proportion to its recruitment; therefore, movements and strategies that require the activation of high-threshold motor units must be incorporated into the training programme for recruitment adaptations to impact sprint performance meaningfully.

– For movement to be both effective and efficient, without impairing sprint technique, agonist activation should be accompanied by increased synergist activity and reduced co-contraction of antagonists.

– Triple extension of the lower limbs, typically observed during jumping and sprinting, involves a complex interplay of uniarticular and multiarticular muscle-tendon units performing coordinated actions.

– Powerful and high-speed actions require precise timing and coordination of agonist, synergist, and antagonist activation and relaxation to optimise power transmission through the kinetic chain and maximise ground impulse, thereby enhancing sport-specific performance (i.e., sprint speed).

– To maximise the transfer of RST to sprint performance, the applied loads should allow for movement velocities that are similar to, or at least close to, those typically encountered in the sport.

Long-term effects of increasing sled and vest loads

The long-term effects of using progressively heavier sled and vest loads remain a topic of debate, and current scientific evidence is still insufficient to demonstrate the superiority of heavy to very heavy loading schemes over lighter loads (e.g., moderate, low, or unresisted) for improving sprint performance [12]. This does not imply that loads greater than ≈ 30% Vdec (≈ 50% BM) should be excluded from training. Instead, it highlights the need for more research to determine whether, after several weeks of training, such loads might negatively impact sprinting mechanics or reduce MSS.

Why are lighter loads (e.g., 2.5% to 20% BM) important? Carlos-Vivas et al. [35] compared the effects of different RST implements (i.e., WV, motorised resistance, combined methods, and UST) using a loading scheme ranging from 10% to 20% BM. They showed that the WV group achieved the most significant improvements in sprint, change of direction, and countermovement jump performance. Nonetheless, significant gains were also observed in the unresisted group for F0, maximal power, MSS, and sprint times. Another study [56] that implemented ST training using two different load types [“light” (10% Vdec) vs. “heavy” (30% Vdec)] reported that the heavy group significantly improved 5–10 m sprint time, whereas the light group exhibited significant improvements exclusively in the 10-metre sprint time. It is worth noting that a 30% Vdec load more appropriately reflects a moderate, rather than heavy, loading condition, emphasising that even low-to-moderate external loads are sufficient to induce meaningful increases in sprint speed. This effect appears to be independent of the training strategy, as moderate (or even lighter) loading conditions, whether applied through ST or WV, have demonstrated comparable effectiveness in improving sprint performance. These loads provide an adequate stimulus to acceleration mechanics and the recruitment of the hip and knee extensors, which are essential for increasing horizontal force application [57].

As practitioners and sport scientists, we may even consider that a given load, specifically heavy and very heavy loads (i.e., > 30% Vdec or > 50% BM), is not detrimental to sprinting technique in the medium to longterm. However, this does not imply that we can indiscriminately or excessively overload ST or WV devices and expect to transform our athletes into exceptional performers, particularly given the well-established limitations associated with the development of acceleration and MSS [58–60]. When prescribing training loads for RST, coaches must consider what is most appropriate for each athlete, taking into account the phase of the season, sport-specific demands, playing position (in the case of team sports), age category, and competitive level. In addition to these factors, it is essential to acknowledge that heavier loads applied during RST sessions are often associated with increased levels of fatigue, metabolic responses, and perceived exertion [38, 47], an undesirable outcome across various sporting disciplines, given the congested schedules that commonly characterise contemporary sport.

Is there any evidence of positive effects on sprint performance with heavy to very heavy loading conditions during sprint training?

A recent narrative review [12] raised a crucial question: what actually defines “heavy or very heavy sled training” or very heavy RST? Should it be considered a form of sprint training, or is it more appropriately classified as a tertiary training method, that is, a method involving non-specific sprint protocols, such as plyo-metric or resistance training exercises [12]? It should be noted that sled loads exceeding 30% Vdec result in athletes no longer sprinting, but rather, at most, running at a moderate pace [12, 37]. As stated above, a prior study found a substantial reduction (≈ 60%) in 20-metre sprint speed in elite rugby players, compared to their MSS over the same distance, when using, for example, a sled load equivalent to 80% BM [37]. In this sense, the following points provide a clear rationale for classifying this training method not as RST, but rather as a complementary (i.e., tertiary) sprint training method, referred to as “heavy sled training” (HST):

– These efforts are performed at very low speeds, resulting in marked alterations in running mechanics and technique, including modified coordination and muscle activation patterns (e.g., significantly lower activation of the biceps femoris long head and higher activation of the rectus femoris), reduced leg stiffness and stride length, as well as increased ground contact time and trunk angle (i.e., the angle described between the shoulder-hip line and the vertical axis during both acceleration and top-speed phases) [40].

– Very short flight time — or even a complete lack of flight time — occurs with sled loads producing a Vdec equal to or greater than 50% (relative to unresisted sprints). Under these conditions, athletes are no longer sprinting or even running; instead, they are effectively marching due to the reduced time available to reposition their limbs for the next step [40].

– These disruptions are proportional to the loading magnitude: the heavier the sled load, the greater the modifications observed in running technique [37, 40].

– The same applies to perceived exertion and metabolic responses, with athletes reporting and exhibiting higher levels of fatigue during and immediately after performing RST with heavier sled loads [38, 47], which, in itself, contradicts the core principle of speed training sessions.

What do we know about the long-term effects of loading conditions greater than 30% velocity decrement on sprint performance?

To date, only three studies [49, 61, 62] have employed experimental intervention designs involving team-sport athletes (i.e., soccer players and high school athletes from rugby and lacrosse). Among the few available investigations, the studies by Lahti et al. [62] and Morin et al. [49] adopted a combined approach when designing the training programmes for the intervention period. Their approach involved a mixed training regimen (i.e., resisted and unresisted sprinting), with unresisted sprints accounting for 34% (50% Vdec group), 44% (60% Vdec group), and 35% (80% BM group) of the total sprint training volume. As such, the lack of clarity in the results may be attributed to the inability to isolate the effects of one training method (i.e., primary training method) from those of the other (i.e., secondary training method). For example, Morin et al. [49] found that soccer players training with 80% BM experienced a moderate positive effect on F0 and a trivial adverse effect on theoretical maximal velocity (V0). Similarly, Cahill et al. [61] reported a trend toward increasingly positive effects as sled load increased (in distances from 5 to 20 m), while a significant decrease in MSS was observed in the very heavy sled load group (75% Vdec). Overall, the study by Lahti et al. [62], involving soccer players, provides valuable insights into this area by presenting data on changes in both kinetic and kinematic variables. Nevertheless, some major limitations reported in the study may have hindered the ability to draw clear and consistent conclusions or to apply their findings in real-world training contexts.

Resisted sprint training: recommendations for prescribing unresisted sprint training, sled-towing, and weighted-vest training loads

Table 3

Summary of the methods used to prescribe sled training loads for sprint performance development

[i] BM – body mass, MRSLT – Maximum Resisted Sled Load Test

Adapted and modified from Zabaloy et al. [11].

First, MSS is a highly complex physical capacity that must be assessed and trained through multiple methods and strategies [13]. Second, faster, stronger, and more powerful athletes require heavier sled loads (relative to %BM) to experience exercise intensities comparable to those of their slower and/or weaker counterparts [63]. Third, when prescribing RST, coaches should consider that heavier loads typically require shorter sprint distances. Fourth, coaches should aim to implement a highly tailored strategy with their athletes, meaning they must individualise not only the external RST load applied to the selected device, but also the total training volume, including sets, repetitions, and distance. Hence, when prescribing sprint training programmes, multiple variables and factors must be carefully considered before implementation. Below, two key aspects are highlighted for practitioners to consider when prescribing RST: (1) the appropriate parameters for selecting training loads, and (2) the appropriate parameters for prescribing training volumes (Table 3).

Once the training method and loading scheme have been determined, coaches must subsequently establish an appropriate strategy for prescribing training volume. This is commonly based on fixed distances or volumes applied uniformly across a group of athletes. Although such an approach offers practical insights, both distance and volume (similar to load prescription) should be determined in accordance with the principle of individualisation [12, 20]. This is particularly relevant given the well-documented interindividual differences observed among athletes competing in the same sport [27,33] (e.g., forwards and backs in rugby union), as well as among those within the same age category (e.g., due to relative age effects). Accordingly, there are two primary methods for prescribing sprint training volume:

– Intra-session training volume adjustment based on Vdec, as described in studies by Grazioli et al. [64] and Jimenez-Reyes et al. [65]. Rather than using a fixed training volume, this method adjusts the volume based on the athlete’s performance decrement within the session. Sprint times or speeds are monitored after each repetition until a predefined %Vdec is reached. For example, if the prescribed distance is 30 m and Athlete A runs the first sprint in 4.00 s, the session would end once their time drops by 2% (i.e., reaches 3.92 s or less), and the athlete would then proceed to the next training block (e.g., technical-tactical drills). This approach can also be applied using jump height decrements (e.g., via jump mats or optical systems), which are monitored after each sprint in the same way as sprint time or speed. When sprint timing technology is unavailable, a meaningful decrease in jump height (i.e., one that can be compared, for example, with the typical variability regularly exhibited by the athlete) [36] is recommended as a practical reference.

– Prescribing the same training volume for the entire group is a simpler and more practical approach, particularly in large-group settings during congested training schedules; however, it does not account for the inter-athlete variability in fatigue responses, physical characteristics, demands, and technical skills.

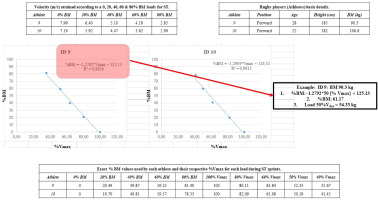

Figure 2

Example of an incremental loading test using sled-towing (ST) sprints in two rugby players, including their individual regression equations used to calculate the target percentage of velocity decrement (%Vdec) loads. Based on data from previous studies [39, 40]

– Recovery intervals should be set at ≈ 1 min for every 10 m of unresisted sprinting. During RST, as the external load increases, these intervals must be progressively adjusted based on the magnitude of the load. For example, coaches may add ≈ 30 s of recovery for light loads, ≈ 1 min for moderate loads, and further extend recovery intervals for heavier loads, based on observed fatigue levels and individual athlete responsiveness.

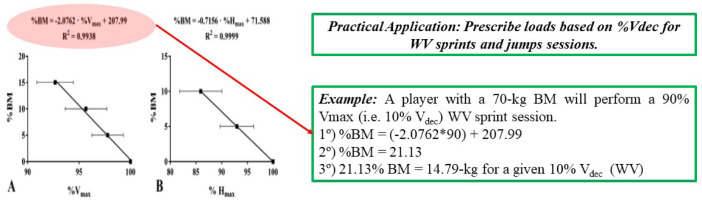

Figure 3

Example of an incremental loading test using weighted-vest (WV) sprints in soccer players. Adapted from a previous study [40]

If coaches choose to prescribe RST loads based on %Vdec, an incremental loading test should be conducted prior to the start of the training period. In the Figure 2, a practical example is provided using an Excel spreadsheet, where the individual regression equation can be used to determine the load required to reach a given %Vdec (e.g., 20% Vdec).

Similarly, if coaches decide to prescribe WV loads based on %Vdec, an incremental loading test should also be performed before the commencement of the training period. In this regard, one could refer to the work of Carlos-Vivas et al. [41], in which the authors provided an easy-to-use tool to monitor the %Vdec and the %BM needed to attain such velocities. Notably, since the latter research was conducted with soccer players, caution should be exercised when applying these data to other sports and athletes. In any case, following the same approach for the incremental WV loading test, the individual regression equation will provide coaches with accurate information to prescribe loads for WV sprinting sessions. Further details are depicted in Figure 3.

Determining the type and magnitude of resisted sprint loads: practical insights derived from rugby union players

To provide some context, rugby players typically participate in one match per week and complete six to seven training sessions across that same period. Recovery following competition may require 48 to 72 hours, assuming proper recovery strategies are available, which is often not the case, particularly in amateur settings. Additionally, the impact of frequent collisions and contact situations must be considered when designing and planning the training programme. In this sense, this is the first and most critical factor to consider when deciding on the appropriate resisted sprint loads for the upcoming training weeks (e.g., typical RST blocks of four to six weeks).

Another key factor involves monitoring the athlete’s performance changes over a given time period. Table 4 presents an example of two players with contrasting profiles, player A (scrum-half) and player B (front row), and their responses to a six-month training period. The delta changes (Δ%) revealed that both athletes showed increased sprint times across all distances (5 to 30 m). The most pronounced negative changes were observed in the acceleration phase (0-5 m), with sprint times increasing by 14% for player B and 23% for player A, indicating that the training programme and competitive demands negatively affected acceleration capacity. Notably, the 30-metre sprint time increased by 6% for Player A, suggesting an overall poor speed adaptation in this athlete. However, the largest contributors to this performance decrement were the negative changes in the initial acceleration phase, which subsequently influenced all split times (10, 20, and 30 m). This pattern is evident in the decreasing Δ% values as the distance increases. While player A showed no change in MSS, Player B demonstrated a 7.7% improvement.

Table 4

Examples of changes observed in two rugby players over a 6-month training and competitive period

Changes in BM must also be considered when evaluating training responses, as increased BM requires greater force application to accelerate the body. Both players showed reductions in initial SM (5-metre SM), clearly associated with impaired acceleration. In contrast, maximum SM increased in both athletes, but for two different reasons: (1) player A maintained MSS but experienced a 3% increase in BM; (2) player B improved MSS by 7.7%, with no change in BM. In both cases, these adaptations resulted in increased SM. From this analysis, it becomes clear that the second key factor to consider when selecting a loading strategy for RST is the need for a comprehensive performance review, ideally incorporating individual kinetic and kinematic data. The given example is based on data from a previously published study involving young amateur rugby players [25].

The contrasting sprint profiles of players A and B suggest that both athletes require a specific intervention to improve their acceleration phase. However, this does not imply that the other sprint phases, such as transition or top-speed phases, should be neglected. Accordingly, training priority should be given to resisted sprints using moderate loads (> 10% to < 30% Vdec) over short distances (5–10 m), supplemented with light loads (2.5% to < 10% Vdec) over medium distances (10–20 m) using sleds or WV, and unresisted sprints over longer distances (20–40 m). The latter category may be more suitable for lighter and faster athletes (e.g., backs in rugby), while being less appropriate for heavier and slower players, such as front row forwards.

In addition to these more practical and simple recommendations, several other resources and factors can be considered and integrated when designing RST programmes for athletes across different sports, including:

– Video analysis, which can help identify technical factors underlying observed performance changes, specifically those related to sprint kinematics.

– Kinetic assessment, especially when using motorised resistance devices (e.g., 1080 Sprint, DynaSys-tem) to measure and evaluate force application patterns and mechanical outputs.

– Comprehensive body composition evaluation, as not all changes in sprint performance can be explained solely by mechanical or technical adaptations.

– Maturity offset is extremely relevant when working with youth athletes, since some performance changes, whether positive or negative, may be more closely related to biological development than to training-induced adaptations.

– Resistance training (strength-power) plays an essential role in developing and maintaining sprint capacity. Therefore, diverse, effective, and well-structured training methods (e.g., complex training, contrast training, cluster sets, Olympic lifts) and exercise types (e.g., ballistic jump squats) should be strategically applied.

– Training frequency, ideally consisting of two to three brief sessions per week, should be adjusted according to the specific phase of the training cycle.

– Training volume, which should be adjusted based on the selected sprint training method. As previously noted, heavier loads require shorter sprint distances (see Table 5 for further guidance).

In summary, the main aspects to be considered regarding the appropriateness and preference for implementing RST with light-to-moderate loads in high-performance sport environments are related to the points listed below:

– RST loads that induce a Vdec greater than 30% of the MSS over the same distance result in substantial disturbances in muscle activation patterns, intermuscular coordination, and running mechanics, leading to a motor action that no longer reflects a true sprinting effort [12].

– MSS is significantly associated with performance in multiple strength-power tests, muscle mechanical properties (e.g., muscle contraction velocity), and lower levels of strength deficit [13, 21, 66]. These close relationships may serve as relevant criteria for load selection during RST.

– To date, no additional benefits have been found for heavy or very heavy RST compared to light-to-moder-ate loading. On the contrary, heavier loads are typically associated with higher ratings of perceived exertion and greater acute fatigue [37, 38, 40], which can be particularly detrimental for elite athletes who train multiple times a day or perform their sprint speed sessions before sport-specific training.

Table 5

Summary of loading strategies and recommended guidelines for sled training prescription based on current evidence

[i] BM – body mass, Vdec – velocity decrement Adapted and modified from: Zabaloy et al. [11]

Conclusions and practical applications

RST has emerged as an applied and effective strategy for improving acceleration and MSS across a wide range of sports and athlete profiles. When appropriately prescribed, RST can provide specific neuromechanical stimuli while respecting sport-specific demands, recovery constraints, and technical integrity. However, its application must be carefully contextualised according to sport type (individual or team-based), training phase, athlete level (e.g., elite sprinters vs. developing team-sport players), and available resources. In court sports, where sprints are very short and frequent, RST should primarily involve short distances (5–15 m) and light loads (2.5–10% Vdec). In team sports with varied positional demands (e.g., rugby, soccer, and American football), RST loads and distances should be adjusted based on individual sprint, strength, and power profiles, as well as BM, playing position, and tactical roles. For instance, heavier and slower athletes may benefit from shorter distances and slightly heavier loads (10–30% Vdec) to increase horizontal force application, while lighter and faster athletes may tolerate longer sprints with lighter loads (2.5–10% Vdec) to enhance MSS [67]. In individual sports, such as track and field (e.g., sprinting events), load prescription must be highly individualised and integrated with technical work, as even minor alterations in sprint mechanics may have significant performance implications. As a final point, it must be emphasised that the UST (i.e., traditional sprints) is widely recognised as a primary and highly effective sprint-specific training method, according to the consensus among some of the leading authorities in the field (e.g., Olympic sprint coaches) [23]. The following recommendations summarise key practical applications of both RST and UST methods that can be implemented across various sports and athletic populations.

– Start with valid and reliable sprint assessments, using TGs over split distances to profile both acceleration and MSS. Such testing forms the foundation for load prescription and subgrouping, especially when training large cohorts.

– When possible, use a Vdec-based load prescription (via incremental loading tests). Loads that induce 10–30% Vdec are typically sufficient to elicit positive neuro-mechanical adaptations without substantially altering technique. Loads exceeding 30% Vdec often lead to excessive deceleration and very slow speeds, disrupted sprint mechanics, and elevated fatigue responses, making them more appropriate as a tertiary sprint training method than as sprint-specific drills.

– When Vdec testing is not feasible, loads can be prescribed using %BM. In this case, loads should remain within light-to-moderate ranges (e.g., 10–30% BM for sleds and 5–10% BM for vests), as interindividual variability increases markedly under heavier loading conditions.

– Sprint distance must be prescribed in inverse proportion to the load: the heavier the load, the shorter the distance. For example, loads above 30% Vdec should rarely exceed 10 m. In contrast, light loads or unresisted sprints can be extended to 20–40 m, especially in exceptionally fast athletes.

– Consistently group athletes when equipment or time is limited. For example, use performance-based thresholds (e.g., load required to induce 10% Vdec) to create subgroups with similar training intensities, thus facilitating session organisation without compromising specificity and effectiveness.

– Manage recovery strategically by adjusting rest intervals according to load intensity and sprint distance. Heavier loads and longer sprints require extended recovery periods, while poorly structured intervals may lead to excessive fatigue and impaired sprint technique.

– Integrate RST with comprehensive performance monitoring, including kinetic assessments (e.g., horizontal and vertical force production), body composition measurements, and technical analysis (e.g., video-based sprint mechanics), especially when working with elite (e.g., world-class sprinters) or developing athletes.

– Always prescribe RST sessions according to the training phase and competitive calendar, with special attention to congested fixture schedules. Lighter RST sessions with moderate loads and lower fatigue cost may be more appropriate when athletes are exposed to high training volumes or competitive demands.

– Avoid prescribing RST with heavy or very heavy loads (> 30% Vdec) as a routine strategy for sprint speed development. Although such loads may increase F0, they often compromise MSS, impair coordination, elevate fatigue levels, and induce movement patterns that diverge significantly from actual sprinting. These efforts should be regarded as complementary forms of strength and power training.

– UST should remain the cornerstone of any serious speed development programme, as emphasised by highly specialised sprint coaches. This approach allows athletes to train at or near MSS under neuromechanically specific conditions, preserving and enhancing sprint technique, while ensuring high transferability to sport-specific performance [23].

– Longer UST efforts (> 30–40-metre sprints) are essential for improving or maintaining MSS, especially in fast, powerful, and technically proficient athletes. Elite sprint coaches recommend prescribing UST under non-fatigued conditions, with full recovery, and integrating timing-based assessments to ensure training quality and progression [22].

By applying these evidence-informed recommendations, practitioners can design effective RST programmes tailored to a wide range of sporting contexts. Whether the goal is to enhance early acceleration in a heavyweight rugby forward, optimise MSS in an elite sprinter, or improve multidirectional explosiveness in tennis players, RST can act as a valuable tool for maximising sprint-related adaptations without compromising technical efficiency or recovery processes when properly prescribed.

Future directions

Future studies should investigate the long-term effects of RST with different loading schemes across diverse athlete populations, including women and youth athletes from various sports [39, 68]. Research is also needed to clarify technical, neuromechanical, and biomechanical adaptations under varying loads, as well as the transferability of these adaptations to sport-specific performance. Finally, integrating advanced monitoring tools (e.g., electromyography and alterations in kinetic and kinematic parameters in elite sprinters) may help refine individualised prescription strategies and optimise sprint development in real-world contexts.