Introduction

Hypopressive exercise (HE) is an exercise therapy program composed of breathing and postural cues that has been popularised in the last decade for the treatment and prevention of a variety of clinical conditions such as low back pain [1], postpartum diastasis recti [2] and pelvic floor dysfunctions [3, 4]. HE is typically delivered by physical therapists or personal trainers in individual or group settings. However, controversy has arisen due to the limited clinical evidence in support of HE [5, 6]. A recent scoping review highlighted the high variability of HE interventions and the lack of reporting program design details in the scientific literature [7].

It has been reported in several reviews on rehabilitation research that descriptions of therapeutic rehabilitation exercise protocols are suboptimal [8, 9]. Exercise-based rehabilitation interventions display a range of complexity and variability of modes that can affect the methodological diversity and replicability and increase the risk of bias [9]. HE is no exception. This technique is often delivered combined with other therapeutic exercises or muscle actions (e.g., pelvic floor muscle training, abdominal draw-in manoeuvre) [7]. HE can be performed in a fitness or clinical setting, at home or supervised, or in group sessions with different populations such as athletes [10], healthy adults [11] or patients [6]. Given its novel, multimodal, and variable nature, a lack of adequate translation of research into practice can ultimately impact the practitioner, patient, and researcher. As such, practitioners’ ability to replicate evidence into practice may be compromised [9, 12], patients’ risk of harm may increase, and researchers’ meta-analytical and systematic synthesis results may be impacted.

A detailed description of the content of interventions and the process of experimental interventions are crucial components of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Several checklists have been developed to aid researchers in adequately reporting and describing exercise intervention details [13, 14]. Among these, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) [13] and the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) [14] are the most widely used and comprehensive evaluation tools for non-pharmacological and exercise interventions, respectively. While TIDieR is commonly applied in clinical and rehabilitative trials [13], the CERT is tailored to the detailed description of exercise programs [14].

To the best of our knowledge, the completeness of reporting in RCTs of HE has not been systematically assessed. The primary objective of this review was to assess the adherence to reporting HE therapeutic interventions as recommended by the CERT and the TIDieR checklists. Secondly, we aimed to assess the methodological quality of HE RCTs with the risk-of-bias tool 2.0 [15], and report on HE intervention characteristics.

Material and methods

Protocol and registration

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist was used for this systematic review [16]. The protocol of this study was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, CRD42 023473434).

Eligibility criteria

The search strategy was developed using the PICO (population, intervention, comparator, and outcome) framework. RCTs assessing HE interventions as a means of therapy for diverse clinical outcomes were eligible for inclusion. The inclusion criteria of the participants/population could include men and/or women with any clinical condition (e.g. low back pain) who underwent a HE-based therapeutic intervention. Interventions that did not include HE were considered as an exclusion criterion. Data only published as abstracts were excluded. Given the aim of this review, the authors of the included studies were not contacted for possible missing information in their manuscripts. Study designs with a randomised parallel-controlled group design, including pilot RCTs, were included. Observational studies, protocols of RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, editorials, reviews, or letters to the editor were not included in this review.

Search strategy

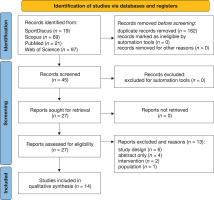

The databases MEDLINE, SportDiscus, Scopus and Web of Science were searched from inception to November 2023. A follow-up search was conducted in May 2024 to identify possible new records. The detailed search strategy is available in Supplementary Appendix 1. There were no filters on the date of publication or language restrictions. The search was restricted to full-text publications. Records retrieved from the aforementioned databases were collected and imported to the reference manager EndNote V.X9 (Clarivate Analytics). All duplicates were removed with the Endnote de-duplicator tool. After the study selection process was completed, the Rayyan QCRI online software was used for screening purposes [17]. Two differentiated levels of screening were performed: (a) title and abstract, and (b) full-text screening. For both levels of screening, two authors (E.H.R., R.M.) independently screened (a) all titles and abstracts identified in the search and determined their eligibility for inclusion, and (b) retrieved agreed citations in full text to be screened independently. The same two authors (E.H.R., R.M.) performed the final inclusion review and data extraction. Disagreements between the main reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (T.R.R.). The output of the searches and screening are presented in the PRISMA-2020 study flow diagram for systematic reviews [16] (Figure 1).

Data extraction and completeness of reporting

Two researchers (H.E.R., T.R.R.) extracted the main characteristics of the included studies as well as the HE intervention details. Supplementary files available from included articles were reviewed as well. Two reviewers (H.E.R., R.M.) assessed the completeness of reporting by using the CERT [14] and TIDieR [13] checklists. Disagreements between the reviewers on both checklist criteria were resolved through a third reviewer (T.R.R.). The TIDieR checklist is based on 12 items (total possible score of 12), while the CERT checklist is based on 16 items (total possible score of 19). The CERT items are divided into 7 sections: what (materials), who (provider), how (delivery), where (location), when and how much (dosage), tailoring (what and how), and how well (planned and actual compliance) [14]. Data was coded and entered in an ad hoc Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

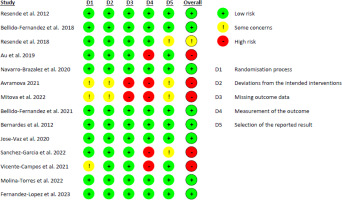

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

All included RCTs were also assessed for risk of bias using the RoB version 2 tool [15]. Each of the tool’s factors was graded as ‘low risk’, ‘some concerns’, or ‘high risk’ [15]. The RoB-2 is based on 5 domains: bias due to the randomisation process, deviations from planned interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and reported outcome selection [15]. Each domain has flagged questions that are enabled depending on the answers to the domain questions. The answers to the questions can be ‘yes’, ‘probably yes’, ‘probably not’, ‘no’, and ‘does not inform’. The tool includes algorithms that assign a bias judgement for each domain. Based on this algorithm, RCTs were classified as ‘low risk of bias’, ‘some concerns’, or ‘high risk of bias’.

Data synthesis

Microsoft Excel was used for descriptive analysis. The total and the individual scores from the TIDieR and CERT checklists were calculated as means, standard deviations, and percentages of reported items. Total completeness of each item and the overall score for both checklists for each study were calculated (from 0% to 100% with 0% representing 0 completeness and 100% full completeness). A score of 1 was given if detailed information was provided and its absence was recorded as 0. We established a cutoff score of less than 60% as low and more than 60% was categorised as ‘high’ following suggestions by previous reports [18, 19]. This cutoff score is obtained by multiplying the reporting score by 100 and dividing by the total possible points on each checklist [18].

Results

The literature search yielded 206 studies, of which 162 duplicates were excluded via automation tools and 31 were excluded for various reasons. 14 RCTs were included. The reasons for exclusion and the corresponding references are reported in Supplementary Appendix 2. The study selection process is provided in the PRISMA diagram flow (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

The included studies were published between the years 2012 and 2023. This review comprised a total population of 782 adults (687 females and 95 males). Included articles evaluated diverse conditions with the application of HE in populations presenting mostly with pelvic floor disorders (n = 8) [20–27], non-specific low back pain (n = 4) [1, 28–30], and rotator cuff injury (n = 1) [31]. Table 1 displays a summary of the main characteristics of the included articles. Of the RCTs included, three were pilot designs [26, 28, 29]. A detailed description of the RCTs’ characteristics is provided in Supplementary Appendix 3.

Adherence to the TIDieR and CERT checklists

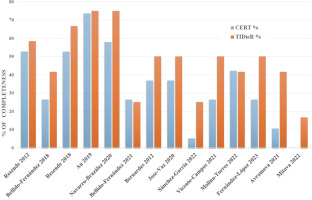

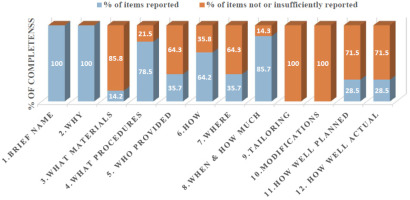

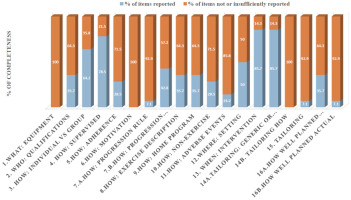

The overall mean average for the TIDieR items for all articles included was 5.7 (SD = 2.1) out of 12 points (47.5%) while the average for the CERT items was 6.4 (SD = 3.9) items out of 19 (33.6%), resulting in low quality of reporting (> 60% of completeness). Figure 2 shows the individual total percentages of reporting for each article on both checklists. Only the study of Au et al. [26] obtained high-quality reporting standards on both assessment tools according to the cutoff score of 60%. Figures 3 and 4 display the results of completeness according to each item from the CERT and TIDieR checklists. The most described items were 1 and 2 (brief name and why) reported by 100% of selected articles, in contrast to items 9 and 10 (tailoring and modifications), which were not reported at all. Item 3 (what) was reported only by two articles (14.2%).

Table 1

Summary of main characteristics of included randomised controlled trials (n = 14)

Figure 2

Percentage of completeness of reporting for each randomised controlled trial on the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) and the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) checklists

Figure 3

Percentage of completeness of reporting among randomised controlled trials for the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist

Figure 4

Percentage of completeness of reporting among randomised controlled trials for the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) checklist

Supplementary Appendix 4 includes the individualised scores for each article for both checklists. The overall mean adherence of reporting CERT items was 4.7 (SD = 3.99) for all included articles. Of note, 66.2% of CERT items were incompletely reported. None of the CERT items was completely reported in the included studies. The items that displayed the highest adherence (85.7%) were those related to the description of the intervention (repetitions, sets, exercises) and the mode of delivery (supervised or not and how they were delivered). The determination of the starting level (how) and progression of HE (tailoring) as well as the extent to which the intervention was delivered as planned (how well) were only reported by one study [26]. On the other hand, what (detailed description of the type of exercise equipment), how (detailed description of motivation strategies), and tailoring (detailed description of how the exercises are adapted to the individual) were not addressed in any study. Only two studies reported the occurrence or non-occurrence of adverse events.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias results of the included RCTs are displayed in Figure 5. Of the 14 RCTs, five were classified as ‘high risk’ [25, 26, 29, 30, 32], one as ‘some concerns’ [22], and eight as ‘low risk’ [1, 20, 21, 23, 24, 27, 28, 31]. Those RCTs classified as high risk were due to methodological issues with outcome measurement (5 studies, 35.7%), the selection of reported outcomes (3 studies, 21.4%), and the randomisation process (3 studies, 21.4%). In 100% of all included articles, domain 1 (bias due to the randomisation process) and domain 3 (missing outcome data) were low risk, with the bias unlikely to significantly alter the results. 28.5% of articles did not report a previous study protocol or trial registration, which led to the decision of ‘some concerns’ (domain 5). Two articles had some concerns and high risk in all five domains [25, 29].

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to assess the quality of reporting integrity and the risk of bias in RCTs using HE for therapeutic purposes. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first review to provide an evaluation of reports in this field. No RCTs met complete adherence to the CERT and TIDieR checklists, and the mean quality of reporting was low (less than 60% of completeness). Our results highlight how incomplete descriptions of HE programs might impact the translation of research into clinical practice. Of concern was the low adherence to the CERT items (33.68%) compared to TIDieR (47.5%). A review of 28 systematic reviews assessing exercise interventions reporting on any health conditions found median poor levels of reporting with the CERT (24%) and TIDieR (49%) [12]. We described similar results where the adherence to the TIDieR items was slightly higher than CERT.

Figure 5

Risk of Bias (ROB) 2.0 judgements according to the domain and overall risk of bias for each randomised controlled trial

A vast majority of included RCTs did not detail relevant information regarding the characteristics of the therapeutic HE program. Items related to the adaptation, modification, and individualisation of the intervention during the study period (e.g., items 9 and 10 of the TIDieR and items 14b and 15 of the CERT) were not detailed. Our findings are similar to other reviews analysing content reporting of exercise-based rehabilitation programs targeting specific health conditions addressed by RCTs on HE, such as pelvic floor muscle training for pelvic organ prolapse [33] or urinary incontinence [34], and Pilates for low back pain [18] or for rotator cuff pain [35].

Similar to other exercise techniques, HE should be contextualised to individual patients’ characteristics and skill level. Some HE poses require certain mobility levels at the hip and spine level (e.g., sitting with legs semi-extended) where some practitioners may need adaptations. Additionally, some patients may require a different progression of intensity of poses and breathing practice. The HE breathing manoeuvre is performed by holding the breath ranging between 3 and 30 s [7]. Practitioners may experience difficulty holding their breath (i.e., beginners or patients with respiratory disease) and therefore may need an adapted progression of the breath-hold. A large proportion of the RCTs failed to detail the progression of breath-holding time based on individual tolerance and dyspnoea levels. This omission limits the replicability of the program and the ability of clinicians to adapt or progress exercise for diverse populations [36]. Similar trends in poor reporting of exercise adaptations were noted in Pilates and pelvic floor muscle training programs for low back pain and pelvic organ prolapse, respectively [18, 33].

Included articles were compared to or used as an adjunct to pelvic floor muscle training for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence. A similar review regarding the completeness of pelvic floor muscle training interventions for pelvic organ prolapse revealed that only 3.8% of the trials described the exercise progression [33]. Concerning the description of the professional guiding the intervention and their degree of experience (item 5 of TIDieR and item 2 of CERT), these were reported only 35.7% of the time. Previous reviews found similar subpar reporting in these items [33, 37]. This is a concern considering that the experience of the person carrying out the intervention can be an influential factor in the results of the interventions [36]. HE can be delivered by health and fitness professionals including nurses, physiotherapists, or exercise trainers with knowledge and experience delivering HE interventions.

Our study found that the name or description of the intervention (item 1, TIDieR) and the rationale, theory or objective of the essential elements for the intervention (item 2, TIDieR) were the best-reported items. These findings agree with other reviews highlighting these items as the most reported items from the TIDieR [33]. However, this is not sufficient to guarantee replicability. Rovira et al. (2024) [7] highlighted the diversity of names attributed to HE in the scientific literature (i.e. hypopressive abdominal gymnastics [38], abdominal vacuum [39], hypopressive abdominal training [40]), which could further hinder interpretation and cause confusion among practitioners.

A key item in reporting exercise interventions is adherence and the mode of assessing adherence. We found suboptimal reporting for item 5 of the CERT (adherence to exercise), item 16a of the CERT (adherence to the intervention), and TIDieR’s items 11 and 12 (adherence was evaluated, how, by whom, and to what extent). Low reporting of adherence, fidelity, and adverse events affects the interpretation of the success and efficacy of HE interventions.

The most common methodological problem in the included studies that resulted in a high risk of bias was a lack of outcome measurement. Several included RCTs did not blind the evaluator. In RCTs exploring rehabilitation exercise, blinding of the treatment arm for the subjects remains a challenge. However, the risk of bias in outcome measurement can be significantly reduced by ensuring the evaluator is blinded. This situation is similar to the article by Satpute et al. [41] in which 13 of the 31 articles on shoulder conditions reviewed presented methodological problems in the blinding of the evaluators. Another methodological problem is the bias in selecting the reported outcomes. Although several included RCTs registered at clinicaltrials.gov before the trial, the intervention, randomisation, and statistical plan were missing or lacked sufficient details to allow an adequate interpretation of the risk of bias. Only Au et al. [26] had a previously published protocol that included detailed information regarding both the trial arms’ exercise program and the progression of exercises.

Despite the CERT and TIDieR checklists being available for use for almost a decade, their adoption by rehabilitation-based trials, including those using HE, is poor [8, 12, 33]. Recent meta-research data [8] showed how the completeness of reporting RCTs published in rehabilitation journals was subpar, where a high risk of bias was associated with worse reporting. Potential reasons for low adherence to exercise reporting checklists include a lack of knowledge by authors and peer reviewers, and restrictions on manuscript submission word counts among scientific journals. The inclusion of mandatory reporting of exercise-based intervention items and the addition of supplementary materials by editors and peer reviewers could enhance the quality of reporting.

There are several checklists adapted from the CERT for specific exercise programs such as the CERT-PFMT [34] for pelvic floor muscle training programs and the CLARIFY-21 for yoga interventions [42]. Although several of the RCTs assessed in our study used pelvic floor muscle training as comparators, and yoga interventions share common features with HE (i.e., similar poses and breathing cues), we selected the CERT [14] because the aforementioned checklists are not specifically adapted to HE. Given the multimodal nature of HE interventions, the development of an adapted checklist for HE components is warranted in future research.

This is the first study to investigate the completeness of reporting of HE with a therapeutic purpose and utilising the most updated tool for risk of bias assessment: ROB-2. We used two complementary checklists because the CERT criteria focus on exercise intervention, whereas the TIDieR criteria are more applicable to clinical interventions. Two authors independently screened, extracted, and graded the tools to minimise possible errors. We did not make any amendments to the initial protocol. However, we did not analyse the relationship between the risk of bias and reporting scores or assess the quality of HE intervention for therapeutic conditions. Although our review included both male and female participants, the majority of the sample consisted of females (87.8%), and none of the included studies performed subgroup analyses by sex. Future HE trials should explore sex-specific outcomes, especially given the use of HE for female-related pelvic floor dysfunctions.

Conclusions

This systematic review found that the completeness of reporting of HE interventions for therapeutic purposes is suboptimal. The most frequent shortcomings were related to insufficient information on planning, tailoring, whether it was planned to be individualised or adapted, and whether there were any modifications throughout the intervention period. Another gap was the lack of sufficient description of how HE protocols were adapted to the participants’ initial fitness levels, as well as how the exercise progressed over time. Comprehensive program reporting is essential to ensure future research replicability, effective implementation by clinicians, and safe application by practitioners.

Although tools like TIDieR and CERT are available and widely recommended, their adoption remains inconsistent within HE RCTs. This lack of detailed program reporting may weaken the interpretation of research findings and clinical translation of future HE interventions. We suggest that researchers comply with therapeutic exercise reporting guidelines and recommend editors and reviewers add reporting checklists to their manuscript submission guidelines to improve methodological transparency. Lastly, the development of a targeted HE-specific reporting checklist, by consensus from researchers and practitioners, may enhance the future quality of reporting HE and aid in bridging the gap between research and practice.