Introduction

Bridging exercises are widely recognised in the field of rehabilitation for their role in managing various conditions in physical therapy practice. Such exercises have been claimed to help encourage prompt weight bearing [1], enhance the stability of the trunk [2–4], and activate key muscles, making them a cornerstone of many rehabilitation protocols [5–7].

In addition to their versatility, side bridge exercises are an essential variation that specifically targets the lateral trunk muscles, contributing to improved core stability and spinal alignment [8, 9]. Their focus on unilateral muscle activation makes them particularly beneficial for correcting strength imbalances between the left and right sides of the trunk [9, 10]. These imbalances are commonly linked to core instability, making them a crucial component of rehabilitation and injury prevention programs [11, 12].

The core musculature, particularly the abdominal muscles, plays a crucial role in various physical activities and daily life functions, including the rectus abdominis, external and internal oblique, which were shown to be important in maintaining postural stability as these muscles are crucial in both producing torque and maintaining spinal stability during axial rotations [13]. The rectus abdominis primarily facilitates flexion of the trunk, drawing the ribcage closer to the pelvis. It also plays a significant role in compressing abdominal viscera and increasing intra-abdominal pressure, which is crucial for actions such as forced expiration, and stabilisation during lifting tasks [14]. While it contributes to overall core stability, its direct contribution to segmental spinal stability is less pronounced compared to deeper core muscles [15], while the external and internal oblique muscles contribute to trunk rotation, lateral flexion, and overall spinal stability. The transverse abdominis, the deepest abdominal muscle layer, increases intra-abdominal pressure and enhances segmental spinal support, particularly during dynamic tasks and forced expiratory efforts [16].

These muscles not only contribute to spinal stability and posture but also aid in respiration and exertion [17]. While the influence of different factors on abdominal muscle activity has been studied extensively, the specific impact of hip angle variations during maximum expiratory effort, particularly within the context of bridging exercise, remains relatively unexplored [18].

Each abdominal muscle is vital for trunk rotation and flexion, and similarly to respiratory muscles, they also perform additional key functions. Firstly, when they contract, they induce an inward pull of the abdominal wall, raising the intra-abdominal pressure. Secondly, they help mobilise the thorax, facilitating breathing. In this role, they are considered strong expiratory muscles and so are crucial for actions like forced expiration [19, 20].

The side bridge exercise, particularly when performed at different hip angles, amplifies these abdominal functions. By varying the hip position (neutral, flexion, or extension), the side bridge targets different abdominal muscle groups, enhancing core stability and improving trunk rotation and flexion. This variation in the hip angle further optimises abdominal muscle activation, making side bridges an effective exercise for strengthening the core, improving posture, and supporting respiratory functions, particularly during forced expiration [3].

Understanding the impact of the hip angle on abdominal muscle activity during maximum expiration can provide valuable insights for exercise prescription, rehabilitation programs, and athletic performance enhancement. Additionally, this research may also contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between respiratory mechanics, core stability, and hip position.

We hypothesised that different combinations of different hip positions and breathing patterns would influence the percent maximum voluntary contraction of RA, EO, and TrA/IO muscles. In particular, we expected that ME combined with hip extension would result in greater activation of the TrA/IO, due to its role in forced expiration and deep core stabilisation. Conversely, we anticipated that RA and EO activation would be more prominent during combinations involving hip flexion and RE, reflecting their contribution to trunk bracing and superficial abdominal tension. Accordingly, this study aims to investigate the influence of combining different breathing patterns with hip positions on the activity of abdominal muscles during side bridges.

Material and methods

Design and sample size

A repeated measures study design was used to examine how different hip positions affect the electromyographic activity of the abdominal muscles – specifically the RA, EO, and TrA/IO – during both RE and ME during the side bridge. The position of the top leg, either in hip flexion or extension, was also varied to assess its influence on muscle activation. The sample size was calculated using G*Power (version 3.1.9.4, Heinrich-Heine-University, Germany) with effect size = 0.8, α = 0.05, power of 80%, number of groups = 1, and number of measurements = 6, for a repeated-measures analysis of variance (within-subject factors). The total sample size was 27. However, 30 participants were recruited because the dropout rate was estimated at 10.0%.

Participants

Thirty healthy male volunteers were recruited through advertisements posted at the university’s physical therapy clinic and a gymnasium in the general university community.

A computer-generated random number table was created using Microsoft Excel. Each participant was assigned a unique identification code, and randomisation was conducted by an independent researcher who was not involved in data collection. To ensure allocation concealment, the testing sequences were placed in opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes. Participants opened these envelopes immediately before testing to determine their assigned sequence.

Participants had a mean age of 21.87 ± 2.58 years, mean weight of 66.03 ± 13.64 kg, mean height of 169 ± 6.51 cm, and mean body mass index (BMI) of 23.00 ± 3.76 kg/m2. Inclusion criteria were: (1) free from musculoskeletal or neurological disorders for at least six months; (2) hip range of motion unrestricted; (3) normal hip muscles (manual muscle test grade 5); and (4) no surgical history that could affect exercise performance. Exclusion criteria were:(1) Female participants, to minimise the influence of hormonal fluctuations, particularly variations in oestrogen and progesterone levels across the menstrual cycle which have been shown to alter neuromuscular function, motor unit recruitment, and muscle fatigue characteristics, all of which can affect EMG activity [21]; Previous studies have demonstrated that changes in estradiol levels, as well as the combined effects of estradiol and progesterone, significantly affect musculotendinous properties and contraction behaviour [22]. Additionally, sex-related differences in lung volumes and respiratory mechanics may impact the abdominal muscle activation patterns during breathing tasks [23, 24]; (2) individuals with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2, to reduce the influence of fatty tissue on signal capturing via EMG; (3) elite athletes; and (4) those engaged in weight training for less than six months.

Measures

Surface electromyography and data recording and processing

We utilised the Biopac AcqKnowledge® surface EMG system to measure muscle activity, which registers and analyses the EMG activity of targeted muscles. The bandpass filter of 20–450 Hz was used and a filter at 50 Hz. The EMG signals were collected at 1000 Hz and converted into a root mean square (RMS) format with a moving window of 10 ms. The middle 5 s of the isometric hold during the activity, from its start to its end, was selected for analysis. Disposable, self-adhesive Ag/AgCl dual snap electrodes (Noraxon Corporate, Scottsdale AZ, United States of America) were used for the sEMG. The electrode characteristics were 2.2 × 2.2 cm of adhesive area, 1 cm diameter of each circular conductive area and 2 cm of inter-electrode distance. Electrode placement followed SENIAM (Surface ElectroMyoGraphy for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles) recommendations and was verified through palpation during voluntary muscle contraction to ensure accurate positioning and signal quality [25]. The reference electrode was placed at the anterior superior iliac spine on the contralateral hand nondominant side. Skin zones for electrode placements were shaved and cleaned with an alcohol swab in order to reduce impedance. An experienced physiotherapist in EMG recording took all recordings.

The disposable EMG electrodes were attached to the abdominal muscles, particularly the RA, EO, and TrA/IO muscles. Proper electrode placement was accurately captured as follows: RA activity 3 cm apart from the umbilicus laterally [11]; for the EO, 15 cm apart from the umbilicus laterally [11, 26]; and for the TrA/IO, the electrodes were placed 2 cm medial and inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) on the ipsilateral side. This location follows established protocols where TrA and IO muscle fibres are anatomically intermingled. Due to their overlap, it is not possible to isolate EMG activity from one muscle without crosstalk. Therefore, the recorded signal is reported as combined TrA/IO activity, which is consistent with previous literature [17]. All electrodes were tested to control for the cross-muscular signal (crosstalk), electrical noise and other interferences in the sEMG signal [27].

Measurements were taken during the side bridge exercise for the muscles on the lower, weight-bearing side. To maintain consistency, the dominant side was tested for all participants. Dominance was defined as the preferred writing arm and kicking leg, and all participants reported right-side dominance. Surface EMG recordings were obtained from the right-side (RA), (EO), and (TrA/IO) muscles. This approach followed previous research assuming bilateral motor symmetry [29, 30] and ensured standardisation across participants [30].

Additionally, an OB-goniometer (OB Rehab Co., Anlic Company, 17182 Solana, Sweden) was utilised to measure the hip angle [31]. The goniometer was positioned near the hip joint in a neutral stance to measure hip range angles. This device includes a fluid-filled box, a gravity-affected needle indicating the reading, and a plate influenced by the magnetic field of the earth. The instrument’s axis was aligned as closely as possible with the joint’s axis and secured with an adaptable strap [32]. The OB-goniometer has a reported measurement accuracy of ± 2° and demonstrates high intra-rater and inter-rater reliability for lower limb joint angle assessment, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) ranging from 0.85 to 0.95 [33]. These features support its suitability for repeated hip angle measurements in biomechanical studies.

Exercising procedure

General MVIC procedure

Before recording measurements, a therapist demonstrated the exercises to all participants, who then performed three test repetitions to ensure familiarity. Participants were kept unaware of their results and the study’s purpose. In order to create a reference for normalisation of the readings, a maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) assessment was measured.

Electromyography was performed for 5 s while maintaining each posture; each procedure was performed twice. A 1-min rest period was allowed between each muscle MVC measurement [34]. All MVICs were performed during breath-holding after normal expiration, to minimise variability in intra-abdominal pressure and muscle recruitment from respiratory effort. In all cases, the resistance was applied isometrically, meaning participants held the position without movement, against the examiner’s force. The EMG amplitudes collected during each exercise were expressed as a percentage of the average MVIC (%MVIC) [35].

The MVICs of the various muscles were measured as follows:

– The MVIC of the RA muscle was measured with the subjects in the supine position with both legs extended, feet fastened, and hands clasped together behind the head. The MVIC of the RA muscle was measured with both shoulder blades raised off the bed and the examiner applying manual resistance cranially on both shoulders [34].

– The MVIC of the EO muscle was measured during leftward trunk rotation. As the right shoulder blade was raised off the bed, the examiner applied manual resistance from the subject’s left side onto the right shoulder [34].

– Finally, the MVIC of the TrA/IO muscles was measured during a rightward trunk rotation. As the left shoulder blade was raised off the bed, the examiner applied manual resistance from the subject’s right side onto the left shoulder [34].

To obtain an MVIC for the EO and IO muscles, each participant adopted a sit-up posture with the torso at approximately 45° in the horizontal position, with the knees and hips flexed at 90° and manually braced by a research assistant [8]. To minimise potential confounding from trunk rotation during side bridging with hip flexion and extension, participants were verbally instructed to maintain a neutral trunk position throughout each trial. A therapist visually monitored the spinal alignment and pelvic position during all repetitions.

These activities were assessed under two breathing conditions: resting expiration (RE) and maximum expiration (ME), during three variations of the side-bridging exercise. Participants received standardised verbal instructions and visual demonstrations on how to perform ME.

They were asked to breathe out maximally and maintain their forced respiration for five seconds and maintain the end-expiratory state throughout each trial [36]. A trained physiotherapist supervised all sessions to ensure correct and consistent breathing performance.

Exercise protocol

Each participant performed the following three side-bridging variations:

– Side bridging (SB): in a side-lying position and a bent lower elbow for more stability, the participant was asked to raise the pelvis off the ground using the elbow and the edge of the ankle. An additional instruction was to keep the body, head to ankle, in a straight line (Figure 1A) [37].

– Side bridging with hip flexion (SB+HF): in the same starting position as in SB, the participant was asked to flex the upper hip at 25°, with the heel of the upper limb positioned in front of the toes of the lower limb. The participant was then asked to raise the pelvis off the ground with support on his elbow and lowermost lateral ankle (Figure 1B) [37].

– Side bridging with hip extension (SB+HE): The participant began in a side-lying position, supported by the lower elbow in a bent position. This time, the subject is asked to extend the upper hip at 25° while keeping the toes of the upper foot posterior to the heel of the lower foot. The therapist asked the participant to elevate their pelvis off the ground, maintaining the side position while resting on the lower bent elbow and the lateral edge of the lower foot Figure (1C) [37].

The draw-in manoeuvre was standardised through a structured familiarisation session. Participants received uniform instructions: ‘Draw in your abdominal wall without moving your spine or pelvis and hold for 10 s while breathing normally’ [38]. A licensed therapist supervised the practice and confirmed proper execution through visual inspection and palpation of the abdominal wall. Participants repeated the manoeuvre under supervision until the correct technique was demonstrated consistently. This procedure was performed in the supine position before each exercise to ensure uniform activation of the deep abdominal muscles.

Figure 1

Demonstration of the side bridge in neutral position (A), side bridge with 25° hip flexion (B), and side bridge with 25° hip extension (C)

During the electromyographic recording, subjects performed a single repetition of each isometric task with a 5 s duration and a 1 min rest between exercises based on previous studies that successfully adopted similar protocols without significant fatigue effects [2, 35]. To minimise order effects and fatigue bias, the sequence of exercises was randomised for each participant. Randomisation was done using a computer-generated random sequence. Each participant received a unique, randomly assigned order of the six conditions. This approach ensured that no single condition consistently preceded or followed another, reducing the risk of systematic fatigue or learning effects influencing the results.

Breathing conditions

Each exercise was performed under two breathing conditions:

– Resting expiration: The participants maintained normal, relaxed breathing during the side-bridge exercises.

– Maximal expiration: Participants were instructed to exhale fully and hold their breath while avoiding using the bracing pattern, which has been claimed to involve an isometric bracing action that simultaneously engages all the abdominal muscles [39]. After maximum expiration, the participant held their breath with an open airway throughout the exercise.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Before testing the proposed hypothesis, the data distribution was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which confirmed significant deviations from normality with a p = 0.001 (p < 0.05). Consequently, nonparametric tests were conducted to maintain the integrity and validity of the analyses.

All participants completed each combination; hence the combinations were treated as one within-group factor. The Friedman test was used to detect significant differences among the combinations for each muscle examined. When the Friedman test indicated significant differences (p < 0.05), further pairwise comparisons were made using Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests.

The absolute value of (r) was utilised to determine the effect size of the differences observed between pairs. An (r) value of 0.1 showed a small effect size, while 0.3 indicated a medium effect size, and greater than 0.5 revealed a large effect size [40].

Results

Table 1 shows the means ± standard deviations of the %MVIC in each of the 6 possible combinations between RE and ME with the side bridge in the neutral position of the hip, with hip flexion and extension, as well as the results of the repeated measures Friedman tests performed to determine whether a significant difference exists between the effects of combinations on the %MVIC of the muscles. For all the muscles selected, the Friedman test revealed a statistically significant difference between the combinations (p < 0.001).

Table 1

Mean and standard deviation for the EMG activity (%MVIC) of RA, EO, and TrA/IO, with comparison differences between different bridging positions

[i] RA – rectus abdominis, EO – external oblique, TrA/IO – transverse abdominis/internal oblique, SB – side bridging, SB+HF – side bridging with hip flexion, SB+HE – side bridging with hip extension, RE – resting expiration, ME – maximal expiration;a highest %MVIC, * significant difference between combinations

Rectus abdominis

The results revealed that when comparing combinations where only RE was performed, no significant difference was detected between any of the positions (p = 0.404–0.688). Similarly, when comparing combinations where only ME was performed, there was no significant difference between any of the positions either (p = 0.385–0.841).

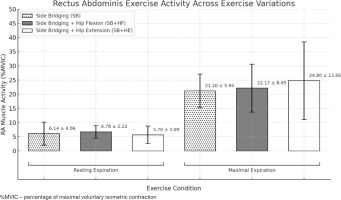

However, when the combinations including RE were compared with those including ME, a significant difference was recorded between all the pairs (p < 0.001), favouring the combinations including ME, which showed higher rectus abdominis %MVIC. This finding shows that the expiration level influences rectus abdominis %MVIC rather than position. Finally, the highest %MVIC recorded was on the side bridging with hip extension and maximal expiration (SB+HE/ME). Figure 2 shows a chart representing the means and standard deviations of the rectus abdominis %MVIC during resting and maximal expirations (Table 2).

External oblique

Similar to the RA results, when comparing combinations where only RE was performed, no significant differences were observed between any of the positions (p = 0.216–0.623). Similarly, when comparing combinations where only ME was performed, no significant differences were observed between any of the positions (p = 0.102–0.316).

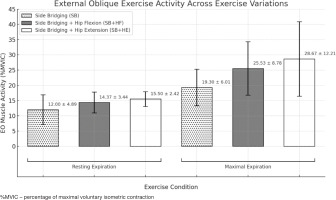

However, when the combinations including RE were compared with those including ME, only side bridging with hip extension and RE compared to side bridging with ME did not show a significant difference (p = 0.082). All other combinations of comparisons showed significant differences (p < 0.001; p = 0.001–0.003). Finally, the highest %MVIC recorded for the EO muscle was observed on the side bridging with hip extension and maximal expiration (SB+HE/ME), similar to that observed with the rectus abdominis. Figure 3 shows a chart representing the means and standard deviations of the external oblique %MVIC during resting and maximal expirations (Table 3).

Figure 2

Normalised electromyography data (%MVIC) of the rectus abdominis during side bridging exercise variations

Table 2

Pairwise comparisons between all the combinations and their effects on the %MVIC of the rectus abdominis muscle

Figure 3

Normalised electromyography data (%MVIC) of the external oblique during side bridging exercise variations

Table 3

Pairwise comparisons between all the combinations and their effects on the %MVIC of the external oblique muscle

[i] %MVIC – percentage of maximal voluntary isometric contraction, SB – side bridging, SB+HF – side bridging with hip flexion, SB+HE – side bridging with hip extension, RE – resting expiration, ME – maximal expiration

* significant difference combinations

The absolute value of (r) equivalent to the effect size in nonparametric testing.

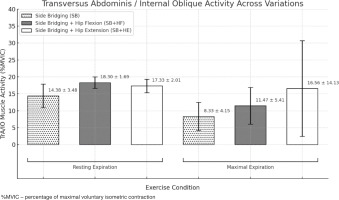

Figure 4

Normalised electromyography data (%MVIC) of the transverse abdominis/internal oblique, during side bridging exercise variations

Table 4

Pairwise comparisons between all the combinations and their effects on the %MVIC of the transverse abdominis/internal oblique muscle

Transverse abdominis/internal oblique

When performing RE, the only significant difference was seen between side bridging and side bridging with hip flexion (p = 0.002). When ME was performed, the only significant difference was seen between side bridging and side bridging with hip extension (p = 0.003), showing that side bridging with hip extension was associated with a higher %MVIC.

Furthermore, when combinations including RE were compared with those including ME, no significant difference was seen when comparing side bridging with hip extension and maximal expiration with its resting expiration counterpart (p = 0.201) as well as side bridging with resting expiration compared to side bridging and hip extension (p = 0.953) and hip flexion (p = 0.171) with maximal expiration. All the other pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences (p < 0.001; p = 0.002–0.003). Finally, the highest TrA/IO, %MVIC was seen in side bridging + hip flexion with resting expiration (SB+HF/RE). Figure 4 shows a chart representing the means and standard deviations of the transverse abdominis /internal oblique %MVIC during resting and maximal expiration (Table 4).

Discussion

The current study revealed significant changes in EMG muscle activity and different breathing patterns during side bridge exercises with varying hip angles. It also showed significant differences in muscle activity between the exercise combinations. For the EO and RA, significant differences were primarily observed between the RE and ME conditions, with ME producing a greater %MVIC. For the TrA/IO, significant differences were mainly between RE and ME.

Concerning RA and EO, our results revealed no significant difference except when we compared combinations including resting expiration (RE) with those including maximal expiration (ME) (p < 0.05), with the latter providing a greater %MVIC. Another study has shown that the rectus abdominis may contribute to stabilising the pelvis by counteracting the anterior pull of the hip flexors during extended hip positions [41]. This suggests that RA activation increases as a compensatory response to maintain pelvic alignment when the torque from hip flexors rises. This mechanism aligns with our finding of increased RA activity during side bridge conditions involving hip extension.

Forced expiration associated with positive pressure would facilitate concentric activation of the expiratory abdominal muscles through increased intra-abdominal pressure, while also noting the importance of considering potential cardiorespiratory strain [42].

These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting increased activation of the EO and IO muscles during forced expiration and variations in trunk posture. For example, full trunk rotation has been shown to enhance left diaphragmatic activity and abdominal muscle recruitment [43].

Another study highlighted the EO and IO muscles’ function during forced expiration. Consequently, they concentrated on forced expiration to improve the effectiveness of these muscles, which led to the recommendations to use forced expiration exercises in people who have limitations in performing regular abdominal exercises [34].

Another study investigated RA muscle activity during a dynamic version of the side bridge, which involved controlled trunk movements rather than maintaining a static hold, as used in our study. Although our design focused on isometric contractions on the supporting side only, the findings are partly consistent [44]. Both studies observed increased RA activation under side bridge conditions, though the dynamic protocol reported greater activity on the mobilised side compared to the stable side. Since our study did not assess asymmetry or dynamic movement, the comparisons are limited, but the trend of enhanced RA involvement under load supports the relevance of side bridge variations for targeting abdominal musculature.

The higher activation of the TrA/IO observed during expiration may be related to its fibre-type composition. A previous study indicates that the transverse abdominis has a greater prevalence of type IIB muscle fibres, which are associated with faster contraction speeds [45]. This histochemical profile suggests that the TrA muscle may be more responsive during rapid, forceful movements such as exhalation. In contrast, the RA and EO muscles may serve different roles due to their differing fibre compositions [46].

Neurophysiologically, the TrA/IO is strongly influenced by the integration of respiratory and postural motor control via shared pathways in the brainstem and motor cortex. Forced expiration increases intraabdominal pressure, enhances feedforward activation of deep stabilisers, and leads to increased recruitment of expiratory motor units [47, 48]. These mechanisms may explain the higher muscle activity observed during ME conditions. Our hypothesis assumed that abdominal activation would vary across breathing patterns and would increase with greater hip flexion during side bridges, due to added trunk demand and co-contraction for stability [20].

When applying side bridge training in practical situations, it is a must to obtain long-term advantages of muscular strength treatments, so researchers should conduct long-term efficacy trials in the future [49].

Furthermore, another study has indicated that altering the trunk posture can enhance EO activity, specifically, forced exhalation. During trunk rotation, a toning effect on the external oblique may occur, as its activity reaches 70% MVIC. Therefore, performing forced expiration in rotation can be suggested as an alternative when EO muscle-strengthening exercise is needed [50].

The number of studies examining the relationship between side bridge exercises, variations in hip angles, and breathing patterns is extremely limited, making it difficult to directly compare all the current findings with previous investigations. However, one study found that side bridge exercises with maximum expiration increased abdominal muscle activity compared to resting expiration, which aligns with the findings of the current study [19].

In other abdominal exercise postures, the activation of the internal oblique during forced expiration remained consistent in both trunk rotation and lateral trunk flexion positions. It has been observed that lower chest wall movement is not restricted during respiration in these positions [43].

Another study suggested that the transverse abdominis is the most activated during RE, followed by the internal and external obliques, while the rectus abdominis showed minimal activation [51]. On the other hand, it has been suggested that forced exhalation during trunk rotation or lateral trunk flexion only changes the activity of the external oblique muscle, without influencing the activity of the internal obliques [50].

Although our study investigated muscle activation during the side bridging exercise, previous research on the curl up exercise has suggested that hip positioning and breathing patterns, particularly ME, can significantly influence the activation of the abdominal muscles, especially the obliques. While the exercises differ in movement and muscular demands, the observed increase in oblique activation with maximal expiration in curl-ups aligns with the trends seen in our findings during side bridging, suggesting a potentially similar underlying mechanism [20].

The effectiveness of changing the hip position in bridging exercises to enhance the activation of specific trunk muscles has been highlighted. For optimal activation of the EO and internal IO muscles, back bridging with hip internal rotation has been recommended [3]. Additionally, for effective activation of the EO and IO muscles during side bridging, positioning the upper hip in either flexion or extension is advantageous. Contrary to the findings of the present study, it has been reported that the activity of the rectus abdominis (RA) does not vary significantly with the hip position [20].

However, it is important to note that the high standard deviations observed in some measurements indicate notable inter-individual variability in muscle activation. This level ofvariation is common in surface EMG studies and may result from differences in muscle recruitment patterns, motor control strategies, and physical conditioning among participants.

Future studies should include both sexes to determine whether similar patterns of muscle activation and breathing interaction are observed. In addition, further studies are warranted to explore how forced expiration in the side bridge position with varying hip angles affects the strength of the oblique, transverse, and rectus abdominis muscles. Therefore, it is essential to investigate simple strategies for enhancing muscle activity in individuals who cannot perform traditional abdominal exercises. It also enhances athletic performance and is beneficial in clinical decision-making related to the prescription of therapeutic exercises. Moreover, these findings should be applied cautiously until further studies report conclusions examining the longstanding effects of side bridge exercises with different hip angles, especially regarding adverse events in specific clinical populations suffering from lumbar pain or inadequate trunk stability who may strengthen their deep abdominal muscles by performing the suggested continuous bridge exercises.

Limitations

A significant limitation of this study is the inclusion of only healthy male participants. This choice, while reducing hormonal variability, limits the gener-alisability of our findings. Females experience cyclical hormonal fluctuations that can affect neuromuscular control, motor unit recruitment, and muscle fatigue characteristics, which are factors known to influence EMG activity. Therefore, the abdominal muscle activation patterns observed in this study may not accurately reflect those in females. As such, our conclusions primarily apply to healthy males and should be interpreted with caution when extended to other populations. Another limitation is that trunk rotation during side bridging with hip flexion and extension was controlled through therapist observation and verbal cues but not measured using validated or objective tools. This may have introduced variability in trunk positioning and should be addressed in future studies using motion analysis systems [52]. While the study concentrated on key abdominal muscles, it did not assess other stabilising trunk muscles such as the erector spinae, gluteus medius, or diaphragm, which also contribute to core stability. Additionally, the study primarily measured EMG amplitude as an indicator of muscle activity but did not evaluate functional performance or endurance, which are crucial for exercise prescription and rehabilitation. This is why further research is warranted to address such limitations.

Conclusions

These findings highlight the importance of considering both hip positioning and breathing techniques for optimising abdominal muscle engagement in exercise prescriptions and rehabilitation protocols. Maximal expiration generally results in greater muscular activity of the RA, EO, and TrA/IO muscles compared to resting expiration, and although hip angle variations showed some inf luence, their effect was limited, especially under resting expiration. Clinicians and fitness professionals should also consider using greater hip flexion angles to increase core demand. These adjustments may improve the effectiveness of trunk stabilisation and rehabilitation protocols.