Introduction

The performance of tennis players does not reside solely in their physical, tactical, technical, and psychological preparation. It can also be influenced by various forms of external motivation, with verbal encouragement from coaches/teachers representing one prominent manifestation that has gained increasing attention in sports psychology research. External motivation encompasses several forms, including tangible rewards, audience effects, and social recognition; however, verbal encouragement represents a remarkably accessible and frequently employed motivational strategy in sports contexts [1]. Over the last decade, it has become increasingly evident that external motivation is crucial for enhancing training, learning, and competitiveness among players and students [2–4]. For instance, Gué-guen et al. [5] have highlighted the significant advantages of verbal encouragement in enhancing learning processes. According to Self-Determination Theory [6], verbal encouragement may facilitate the internalisation of extrinsic motivation, potentially enhancing athletes’ sense of competence and relatedness – two fundamental psychological needs that contribute to optimal functioning and well-being. Verbal encouragement methods, such as compliments like ‘You are good’, ‘You are capable’, and ‘You can do better’, have been shown to improve performance and boost confidence levels and are particularly relevant for athletes and students, who can significantly benefit from verbal encouragement during activities and tasks.

Verbal encouragement is a powerful tool for enhancing physiological and psychological responses related to motivation in athletes involved in high-intensity activities; however, its effectiveness may vary based on individual differences, such as personality traits, experience level [7], and personal preferences for feedback [8]. Studies have also shown that player-athletes become more engaged in a task when receiving verbal encouragement from coaches, and the positive effects of encouragement become more apparent when high-intensity exercise is elicited [3, 4, 9]. Tennis presents a unique context for studying the impact of verbal encouragement due to its intermittent nature, alternating between high-intensity rallies and recovery periods, combined with its considerable mental demands as an individual sport where players must independently regulate their effort and emotional responses [10]. The study by Selmi et al. [9] showed that verbal coach encouragement had a positive effect on soccer players’ heart rate, rate of perceived exertion (RPE), and level of pleasure. According to Sahli et al. [4], coaches who provide verbal encouragement to their players can increase their motivation and physical commitment during the game. Verbal encouragement may improve mood, self-confidence, RPE, and overall physical enjoyment [4, 9, 11, 12].

Verbal encouragement from teachers or coaches appears to have beneficial effects across various sports contexts [4, 9, 13]. However, the transferability of findings between team sports, such as soccer, and individual sports, like tennis, requires careful consideration due to their distinct psychological and physiological demands [14]. Studies conducted in these contexts have demonstrated positive effects on the physical, psychophysiological, and pedagogical domains [4, 9, 15]. In this direction, Kilit et al. [16] investigated the impact of coach verbal encouragement on psychophysiological parameters and physical performance in young tennis players, and the results reported that verbal encouragement from coaches during play situations, in particular with a high intensity, can lead to better results in physical, psychophysiological, and emotional parameters.

Providing that positive feedback and support can enhance the performance and motivation of individuals during challenging physical activities [17], along with recognising the importance of creating supportive and encouraging environments in sports and fitness settings for the adherence and development of young athletes [18] and understanding that knowledge regarding how verbal encouragement affects effort intensity and performance in tennis athletes remains limited, with particular gaps concerning its application in youth populations where developmental factors may influence receptiveness to external feedback [19]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of the coach’ verbal encouragement on the perceived effort, mood state, and performance in young tennis players during matches. Specifically, the impact of verbal encouragement on the ‘Profile of Mood States (POMS)’, the total mood disorder (TMD), the RPE, and tennis match performance was examined. Based on previous research, we hypothesised that coach verbal encouragement would: (1) positively impact mood states by reducing total mood disturbance scores; (2) sustain higher levels of perceived effort throughout match play; and (3) improve overall tennis performance as measured by successful ball scores. We anticipated that psychological effects, such as mood improvements, might demonstrate stronger responses than performance metrics, consistent with findings from studies in other sports contexts [9].

Material and methods

Study population

Ten young tennis players (6 males and 4 females, mean age: 9.10 ± 0.99 years, body mass: 23.32 ± 3.65 kg, body height: 1.21 ± 0.04 m, body mass index: 15.87 ± 2.35 kg · m–2, and body fat percentage: 14.51 ± 3.32%) voluntarily participated in the study. This age group (8–10 years) was specifically selected as it represents a critical developmental period when children begin to develop sport-specific skills while remaining highly receptive to adult feedback and reinforcement [20]. At this developmental stage, children typically exhibit increased responsiveness to external motivational cues while continuing to develop their intrinsic motivational systems [21]. Inclusion criteria consisted of a minimum of 2 years of tennis training experience and being currently injury-free. Players trained four times per week. Each training session lasted for one hour. Before the study began, medical questionnaires were completed, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Parental signed consent was also obtained for subjects under 18 years of age. The protocol adhered to internationally accepted policy statements regarding the use of human subjects, as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Tunisian Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education approved the study.

Sample size

The sample size was determined a priori using the open-source software G*Power® (version 3.1, Düsseldorf, Germany). To do this, we considered the F statistic for repeated measures and hypothesised an eta-squared of 0.2, resulting in an effect size of 0.50. In this regard, we used a standard alpha of 0.05 and a beta of 0.95 for eight repeated measures. The minimum recommended sample size was seven subjects (power: 0.96, critical F: 2.23). Therefore, to avoid potential sample losses, 10 subjects were included in the final sample of this study. While statistically powered to detect moderate to large effects, we acknowledge that this relatively small sample size may limit the generalisability of our findings to broader populations. However, the crossover design mitigates some of these limitations by controlling for individual differences through within-sub-ject comparisons [22].

Procedures

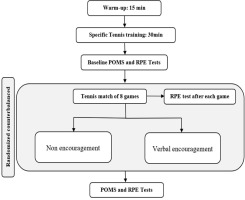

A randomised crossover design was selected to enhance the internal validity, as it allows each participant to serve as their own control, thereby reducing the inter-individual variability and increasing the statistical power with a relatively small sample size [23]. This design is particularly advantageous for studies examining acute interventions where practice effects are minimal and washout periods can effectively eliminate carryover effects [24]. All testing was conducted during the pre-competitive training phase in September and October, from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Before arriving at the testing field, all subjects were asked to consume their normal morning snack, hydrate for testing, and refrain from engaging in strenuous exercise for 48 hours prior to testing. For the evaluations, athletes completed three initial sessions on separate days to collect physical characteristics (session 1) and to familiarise themselves with the ‘Profile of Mood States’ (POMS) and RPE questionnaire protocols (sessions 2 and 3). The latter was done to ensure that all procedures were fully understood and could be executed correctly. Testing was grouped and conducted cyclically to minimise be-tween-trial circadian variations in POMS and RPE expressions. All testing sessions for each participant were conducted at consistent times (within ± 30 min) to control for potential diurnal fluctuations in performance and psychological measures [25]. One week following the completion of the initial sessions, each subject performed two testing sessions during two consecutive weeks. To account for potential order effects, participants were randomly assigned to sequence groups (encouragement-first or control-first) using a blocked randomisation design. Statistical analyses confirmed no significant order effects (p > 0.05) for any outcome measure.

In each testing session, subjects were assigned to one of the two encouragement conditions: non-encouragement and positive verbal encouragement. Subjects were randomly assigned to perform the two experimental conditions with the help of an online random number generator (Research Randomizer 4.0). A minimum of 48 hours and a maximum of 72 hours were permitted between testing sessions to ensure adequate recovery while minimising detraining effects [26]. This interval was specifically selected based on research demonstrating that young tennis players typically recover physiologically and psychologically from competitive play within 24–48 hours [27], while avoiding potential skill decay that might occur with longer intervals. In each testing session, subjects completed the same pre-match training load (30 min of specific tennis training), and POMS and RPE were collected 5 min afterwards, to establish baseline values, as well as after the 8-game match routines (Figure 1). RPE was also assessed after each game. This is also useful for determining natural day-to-day fluctuations in performance.

Successful balls were operationally defined as points won by the players after engaging in one or more rallies (minimum of two-shot exchanges) with their opponents during the match. This definition excluded points won through opponents’ double faults or unforced errors on the first shot, thereby ensuring that successful ball scores reflected the player’s actual performance rather than opponent mistakes [28].

The verbal encouragement protocol was standardised as follows:

– The coach positioned himself at a consistent distance (approximately 2 m) from the court and within the peripheral visual field of the target participant, maintaining this position throughout the match.

– Encouragement was delivered using a standardised set of motivational phrases (e.g., ‘Bravo!’, ‘Excellent effort!’, ‘Well done!’, ‘Keep going!’) at regulated intervals (after each point and during changeovers).

– The tone, volume, and enthusiasm of delivery were practiced and calibrated before the study to ensure consistency across all participants [29].

– Encouragement maintained a positive focus regardless of point outcome, with supportive statements following lost points and reinforcing statements following won points.

Rate of perceived exertion test (RPE)

The RPE is an evaluation commonly used to measure the intensity of effort provided during a match or training session and the level of fatigue that the subject experiences [30]. The RPE was calculated using the Perceived Fatigue Estimation Scale. Many RPE scales have been created, but the Borg scale modified by Foster et al. [30] consists of 11 levels (from 0 to 10). Each estimate was recorded immediately at the end of the game using a standardised questionnaire: ‘How did you feel about the match?’.

Profile of Mood States Test (POMS)

The POMS was used to measure mood state. This self-assessment questionnaire comprises 65 adjectives designed to assess six states: tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, vigour-activity, fatigue-inertia, and confusion-perplexity [31]. Responses to each item are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 indicates ‘not at all’ and four means ‘extremely’). The six POMS subscales can be combined into a total mood disorder (TMD) score by adding the T-scores for the five negative mood subscales and subtracting the T-score for the positive mood states by adding a constant of 100 to avoid negative numbers {TMD = [(anger + confusion + depression + fatigue + tension) – vigour] + 100}. The subjects answered the questionnaire individually.

Before each testing session, participants completed a brief questionnaire assessing potential confounding factors, including sleep quality the previous night (rated on a 1–5 scale), perceived stress levels (rated on a 1–5 scale), and any unusual events that might have influenced their mood or performance. No significant correlations were found between these factors and outcome measures (all r < 0.3, p > 0.05), suggesting that external factors had minimal influence on the study results.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations (SD), were calculated after confirming the normality of distributions using the Shapiro–Wilk test. To mitigate the risk of Type II errors, we reported estimates of power (ω) and effect size (partial eta squared, η2p), with the η2p values interpreted as small (0.01–0.05), medium (0.06–0.13), or large (> 0.14) effects [32]. Following significant factor interactions, Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise post-hoc tests were performed. Effect sizes for pairwise comparisons were calculated using Cohen’s d, with values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 representing small, medium, and large effects, respectively [32]. A 2 × 2 repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to analyse the effect of verbal encouragement and time on the POMS scores, while a 2 × 9 (condition × time) repeated-measures ANOVA was used for the RPE scores. When appropriate, Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise post-hoc comparisons were conducted. We assessed both the inter-trial and intersession reliability of the POMS and RPE measurements. Relative reliability was determined by calculating an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using model 3,1. Absolute reliability was expressed in terms of the standard error of measurement (SEM) and coefficients of variation (CVs) [33]. Finally, we examined heteroscedasticity to ensure the consistency of measurement error across the range of observed values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Inter-trial and intersession reliability of POMS and RPE

The pairwise analysis of TMD and RPE indices revealed no significant difference between trials and sessions [p > 0.05; d: 0.02–0.16 (trivial)]. The TMD index displayed ‘moderate’ inter-trial [ICC(3,1) = 0.74] and inter-session [ICC(3,1) = 0.61] relative reliability with excellent absolute reliability (CV: 1.41%–1.82% and SEM: 0.72%–1.13%) (Table 1). In both the inter-trial and inter-session assessments, the RPE index showed ‘good’ relative reliability [ICC(3,1) = 0.79–0.82], but demonstrated ‘poor’ inter-session absolute reliability (SEM = 5.09% > 5% and CV = 11.4 > 10%). This pattern of reliability metrics for RPE is consistent with previous findings in youth populations, reflecting normal day-to-day variability in perceived exertion ratings among developing athletes rather than measurement instability. Moreover, there was no heteroscedasticity in the raw data (r = – 0.09 to 0.16; p = 0.23 to 0.62) (Table 1).

Table 1

Inter-trial and intersession relative and absolute reliability of POMS and RPE indices (n = 8)

Effect of verbal encouragement on TMD scores

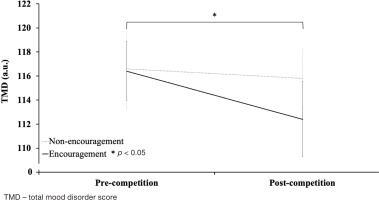

There was a statistically significantly small effect of the encouragement [p = 0.017, ηp2 = 0.49 (small), ώ = 0.74] and time [p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.88 (moderate), ώ = 0.74] factors with a significant interaction between the encouragement and time factors [p = 0.025, ηp2 = 0.45 (small), ώ = 0.67)] (Table 2). Pairwise comparisons at post-competition showed that the TMD score was significantly lower following ‘verbal encouragement’ [p = 0.014, d = 0.93 (moderate)] compared to the non-encouragement condition (Figure 2). In addition, for the ‘verbal encouragement’ condition, the TMD scores decreased significantly [p < 0.001, d = 1.44 (large)] after the competition compared to the pre-competition scores (Figure 2). To contextualise these statistical findings in practical terms for youth tennis contexts, the 2.9% reduction in TMD scores following verbal encouragement represents a meaningful shift in psychological state during competitive play. Based on established minimal clinically significant difference thresholds for mood assessments in youth sport, this magnitude of change likely reflects a practically significant improvement in emotional state that could enhance training adherence and sport enjoyment, which are critical factors for long-term athletic development in this age group.

Table 2

Effects of verbal encouragement and time on POMS and RPE indices scores (n = 10)

Effect of verbal encouragement on RPE scores

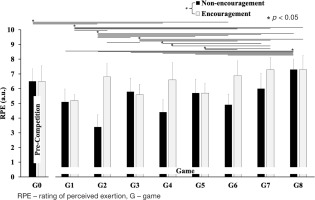

There was a significant effect of the encouragement [p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.78 (moderate), ώ = 1.00)] and time [p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.57 (small), ώ = 1.00] factors with a significant interaction between the encouragement and time factors [p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.69 (moderate), ώ = 1.00, Table 2]. In 50% (e.g., games 2, 4, 6, and 7) of the games, the RPE scores were significantly [p = 0.001–0.009, d: 0.61–2.58 (moderate-large)] higher in the ‘encouragement’ condition compared to the non-encouragement condition. For the ‘non-encouragement’ condition, pairwise comparisons of RPE scores between games (Figure 3) showed various significant differences [p = 0.001–0.048, d: 0.43–2.17 (small-large)] with an unstable variation (i.e., progression or regression) of RPE. While in the ‘encouragement’ condition, RPE demonstrated more stable progression throughout the entire match, with two distinct effort intensification phases: first during the 3rd game [p = 0.007, d = 1.19 [large)] and again during the 7th game [p = 0.001, d = 2.63 [large)]. This pattern suggests verbal encouragement enabled more systematic effort regulation during match play, potentially preventing premature fatigue during early game stages while facilitating appropriate effort elevations at strategically important match points.

Figure 2

TMD scores in pre- and post-simulated tennis competition for the two encouragement conditions

Figure 3

RPE scores in pre- and post-simulated tennis competition for each game in the two encouragement conditions

Table 3

Effects of verbal encouragement and time on successful balls during simulated tennis competition (n = 10)

Effect of verbal encouragement on tennis game performance

For successful balls scores over the games (Table 3), there was a significant effect of the encouragement [p = 0.049, ηp2 = 0.37 (small), ώ = 0 .53] and no significant effect of time [p = 0.874, ηp2 = 0.05 (trivial), ώ = 0.18] factors with no significant interaction between the encouragement and time factors [p = 0.401, ηp2 = 0.11 (trivial), ώ = 0.42].

Individual response patterns to verbal encouragement

While group-level analyses provide valuable insights into the overall effects of verbal encouragement, the examination of individual response patterns revealed notable inter-individual variability. Eight of 10 participants (80%) showed consistent improvements in mood states with verbal encouragement, while two demonstrated minimal changes (responders vs. non-responders). For RPE responses, we identified three distinct response patterns: (1) ‘progressive responders’ (n = 5), who showed steadily increasing RPE with verbal encouragement, (2) ‘threshold responders’ (n = 3) who, maintained a stable RPE until specific game points, where effort suddenly increased, and (3) ‘inconsistent responders’ (n = 2), who showed variable RPE patterns regardless of the encouragement condition. These individual response variations highlight the importance of considering personal factors when implementing verbal encouragement strategies in youth tennis contexts.

Discussion

The main findings of the current study were that the TMD score after competition was significantly lower in the ‘verbal-encouragement’ condition compared to the non-encouragement condition and also compared to the pre-competition scores. The TMD and the RPE indices displayed ‘moderate’ to ‘good’ reliability, while the RPE index showed ‘poor’ inter-session absolute reliability. RPE indexes during games 2, 4, 6, and 7 were significantly higher in the ‘encouragement’ condition compared to the non-encouragement condition. In the ‘encouragement’ condition, RPE was more stable and increased progressively throughout the entire match, with two distinct thresholds observed during the 3rd and 7th games. Successful ball scores over the games were not significantly affected by the time or encouragement conditions.

This study examined the impact of verbal encouragement from coaches on the psychophysiological responses and performance outcomes of young tennis players. Our findings contribute to the growing body of research examining coach-athlete interactions in youth sports contexts, with particular relevance to individual sports, where external feedback may play a distinctive role compared to team settings. By examining the differential effects of verbal encouragement on mood states, perceived effort, and performance metrics, we provide evidence regarding both the benefits and limitations of this coaching approach.

Our findings regarding mood enhancement align with previous research by Sahli et al. [4] and Selmi et al. [9], who reported similar positive effects of verbal encouragement on mood in soccer players. However, our study extends these findings to an individual sport context with younger participants, suggesting the mood-enhancing effects of encouragement may transcend both sport type and developmental stage. Interestingly, the lack of performance improvement despite psychological benefits contrasts with findings by Kilit et al. [16], who reported enhanced technical performance with verbal encouragement in young tennis players during training exercises. This discrepancy may reflect differences between controlled training environments and competitive match settings, where performance is influenced by interactions with opponents and tactical considerations beyond motivational factors [29]. Extrinsic motivation has been shown to have positive effects on physical engagement, good behaviour, and the desire to train [16]. By using verbal encouragement with sports practitioners, coaches can also tap into the natural tendencies of active engagement and provide positive feelings during physical exercise [34], which has a profound impact on intrinsic motivation [35], desire, and pleasure in performing an exercise. The study by Sahli et al. [4] on the role of verbal encouragement in changing the mood of young male soccer players during small-sided games showed that verbal encouragement had a significant impact on the players’ mood. The researchers also reported that verbal encouragement is an external motivation imposed by coaches during training sessions. By combining extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, coaches can create a powerful environment that inspires athletes to reach their full potential.

The 2.9% reduction in TMD scores in the verbal encouragement condition represents both statistically and practically significant improvements in mood state. This positive psychological shift likely operates through multiple mechanisms. First, verbal encouragement may buffer against competition-induced stress by activating the prefrontal cortex regions associated with positive emotional processing [18]. Second, encouragement likely enhances perceived competence – a key psychological need identified in Self-Determination Theory that facilitates the internalisation of motivation [36]. Third, verbal encouragement may serve as a cognitive distraction from fatigue and performance anxiety, enabling players to maintain more positive affective states throughout the competition [37]. Post-competition TMD scores in the verbal-encouragement condition were 2.9% lower than those of the non-encouragement condition, and 3.4% lower than pre-competition scores. Verbal encouragement may have a significant positive effect on a tennis player’s performance. However, this effect is not solely about saying positive words. The timing and frequency of encouragement are relevant; for example, if a player is struggling and feeling discouraged, hearing ‘You can do it!’ might be more helpful than hearing it when they are already feeling confident. Moreover, excessive encouragement can be overwhelming and distracting, while insufficient encouragement may have no effect at all [38]. Intensity is another factor that influences the impact of verbal encouragement. Shouting ‘Come on!’ might be motivating for some players, but it can also be perceived as aggressive or intimidating for others. Furthermore, the terms used for encouragement matter, as some players may prefer technical feedback, while others respond better to emotional support [39].

The interaction between exercise intensity and verbal encouragement appears particularly significant for optimising psychological responses. Selmi et al. [9] demonstrated that high-intensity intermittent training (HIIT) combined with verbal encouragement produces synergistic effects on mood states in soccer players. This synergy may be explained by intensity-dependent neurophysiological mechanisms, including enhanced endorphin release and catecholamine response during high-intensity efforts [40], which verbal encouragement may further amplify. Additionally, encouragement during high-intensity efforts may increase athletes’ perception of social support precisely when the physiological demands are most significant, thereby transforming potentially negative perceptions of discomfort into more positive interpretations of productive effort [41]. It is reasonable to assume that verbal encouragement can positively influence the mood of tennis players, particularly when combined with high training intensity [42]. Verbal encouragement from the coach can have a significant impact on the emotional state of players [9, 16] and, in turn, improve their performance. Positive feedback and motivational words can boost confidence, reduce anxiety, and increase motivation, leading to better focus and concentration during training or competition. Moreover, verbal encouragement can enhance physiological responses by increasing their heart rate, blood pressure, and adrenaline levels [4, 9, 43], which are essential for optimal performance.

In half of the games analysed (games 2, 4, 6, and 7), the RPE scores were significantly higher in the ‘encouragement’ compared to the ‘non-encouragement’ condition. The non-encouragement condition showed erratic RPE fluctuations, indicating inconsistent effort allocation (Figure 3). In contrast, the encouragement condition produced more stable and progressively increasing RPE throughout the match, with significant thresholds during the 3rd and 7th games. This stabilising effect on effort perception likely occurs because verbal encouragement helps athletes maintain an at-tentional focus on the task rather than on fatigue sensations [44]. Additionally, encouragement may enhance self-efficacy, which has been shown to moderate the relationship between physiological effort and perceived exertion [45]. The specific threshold points at games 3 and 7 coincide with critical tactical junctures; game 3 represents the early adaptation phase, when players establish match rhythm, and game 7 represents the decisive closing phase, when outcome pressures typically intensify [46]. Our results align with some previous research [9, 47]. The study by Rampinini et al. [47] showed that the RPE is greater in amateur soccer players (age 24.5 ± 4.1 years) in small-sided soccer games when the coach provides verbal encouragement. Similarly, Selmi et al. [48] found that RPE and maximum heart rate were higher in professional footballers who played reduced games with encouragement compared to those without encouragement. Alternatively, a recent study by Selmi and Bouassida [49] has shown that training without verbal encouragement from the coach may lead to an increase in mood disturbances and a decrease in RPE. Altogether, this suggests that verbal encouragement from the coach is effective at increasing the intensity and motivation of the players.

Our study supports that coaches should be mindful of how to use verbal encouragement with their players to maximise their performance and motivation on the court. Moreover, they should consider incorporating verbal encouragement and high-intensity training sessions into their training program to improve the mood, intensity, and overall engagement of their athletes. While our findings suggest overall benefits of verbal encouragement on psychological states and effort regulation, the individual response patterns revealed in our analysis highlight important considerations for practical application. Previous research has demonstrated that athletes’ responsiveness to verbal encouragement can vary significantly based on factors such as personality traits (particularly extraversion and neuroticism), preferred attentional focus styles, and prior coaching experiences [50]. Van Raalte et al. [51] found that some athletes prefer instructional feedback during competition. In contrast, others respond better to motivational encouragement, suggesting the need for individualised approaches to verbal feedback during tennis matches. Further research is necessary to fully understand the role of verbal encouragement in tennis players throughout the games of the matches.

Several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting our findings. First, the absence of physiological measurements (e.g., heart rate variability, salivary cortisol, blood lactate) limits our ability to correlate subjective experiences with objective physiological responses. Such measures would provide valuable insights into the psychophysiological mechanisms underlying the effects of verbal encouragement. Recent advances in non-invasive monitoring technologies make such measures increasingly feasible in field settings with youth populations [52]. Second, our controlled match environment differs from tournament settings, where additional factors such as audience presence, ranking implications, and performance expectations may moderate the encouragement effects. Third, despite standardising our verbal encouragement protocol, individual interpretations of encouragement phrases may vary based on prior coach-athlete relationships and personal preferences for feedback [53]. Future research could enhance the investigation of psychophysiological parameters such as well-being indices, self-confidence, and their effects on technical aspects and physiological responses during games and training sessions.

For coaches working with young tennis players, our findings suggest several practical applications. First, systematic verbal encouragement appears particularly valuable for enhancing mood states and maintaining consistent effort, even when immediate performance improvements are not evident. Second, encouragement timing may be optimised by concentrating motivational feedback at critical match junctures – particularly during early adaptation phases (around game 3) and closing phases (around game 7) – when effort regulation appears most responsive to external input. Third, coaches should consider developing individualised encouragement approaches tailored to player characteristics and preferences, potentially assessing individual responses during training sessions before implementing these strategies in competitive settings. Fourth, coaches should recognise that while encouragement may not produce immediate performance improvements in match settings, the psychological benefits may contribute to enhanced training adherence and long-term development [54].

Conclusions

In conclusion, verbal encouragement from coaches produces significant acute benefits for the psychological well-being of young tennis players by enhancing mood states and facilitating more systematic effort regulation throughout match play. However, these psychological and effort-related improvements did not translate into immediate performance enhancements as measured by successful ball scores. This dissociation between psychological/effort responses and performance outcomes highlights the complex relationship between motivation, effort perception and technical execution in youth tennis contexts.

These findings have important practical implications for youth tennis coaching. Verbal encouragement should be strategically implemented as a tool for psychological development and effort optimisation, rather than as a direct performance enhancement technique. Coaches may benefit from incorporating structured encouragement protocols to promote positive psychological states that support long-term athlete development and sport engagement. The observed mood benefits may prove especially valuable for sustaining motivation and promoting adherence among young athletes, which are factors that significantly influence longterm participation in sports.

Future research should extend these findings in several directions. First, longitudinal studies examining whether consistent application of verbal encouragement over extended periods eventually translates into performance improvements through psychological skill development would provide valuable insights into potential delayed performance benefits. Second, investigations exploring how verbal encouragement interacts with different training intensities and competitive pressures may help optimise encouragement protocols for specific training phases. Third, examining how individual differences in personality, motivational orientation, and developmental stage moderate responses to verbal encouragement would facilitate more personalised coaching approaches. Finally, incorporating physiological measures, such as heart rate variability and salivary cortisol, alongside psychological and performance metrics, would enhance the understanding of the psychophysiological mechanisms underlying the effects of verbal encouragement.