Introduction

Cervical radiculopathy (CR) is a neurologic disorder that arises due to inflammation and compressed cervical nerve roots because of herniation of a cervical disc, cervical osteophytes, or spondylosis [1]. The clinical signs of CR show severe pain in the neck and a radiating sharp pain with burning or numbness sensation within the upper limb dermatomal distribution of the nerve, which is provoked by the movement of the neck, which leads to increased muscle and soft tissue tension producing movement restrictions [2]. Myofascial release (MFR) is an approach that concentrates on the removal of movement restrictions from the body’s soft tissues, which is projected to decrease pain and improve movement in chronic pain conditions. This therapy helps in the recovery of the fascia connective tissue by applying fascial release and pressure, therefore, the gentle slow pressure of MFR permits the tissues to rearrange, removing the physical restrictions [3].

The MFR enhances blood circulation, which reduces the fibrous band pressures of the connective tissue. It is hypothesised that the MFR leads to changes in tissue texture and tension due to the dynamic alternation in the neuromuscular systems and connective tissues of the body [4], and improves the imbalance of muscles with the protection of its length and function, including the application of one of the essential cervical gross MFR methods that comprise the “arm pull technique” which is the upper quarter gross stretch and posterior cervical spine gross stretch [5]. The characteristics of these techniques are joint stress relief, improving musculotendinous junction extensibility, neuromuscular efficiency, modifying the imbalance in muscles, and preserving the muscular length during normal function [5].

Several myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) on the side of radiculopathy were found in patients with CR [6]. Although many therapies are applied for CR, significant evidence concerning the role of gross MFR in patients with CR is still lacking, therefore this study’s main aim was to explore the role of gross MFR combined with the selected designed treatment on pain, range of motion, function in patients with CR, aiming to improve the physiotherapy rehabilitation in cervical disorders. The current study hypothesises that cervical gross MFR would not improve function and pain in patients with CR.

Material and methods

Study design

A two-arm, parallel randomised controlled trial was achieved through concealed distribution and a blinded assessor, including two groups for every group of 20 patients allocated randomly. The study group received gross MFR therapy combined with the selected, designed program, while the control group received the selected, designed program, for 3 sessions weekly for 4 weeks.

Randomisation

An independent researcher was responsible for the randomisation procedure. The patients were randomly divided using the opaque closed envelope method. Following randomisation and intervention, no subjects dropped out of the trial (Figure 1).

Participants

Forty patients with CR were diagnosed and referred by a neurologist according to neurological examination with dermatomal affection and signed a consent form. The patients included meet the following criteria: age from 30 to 45 years old with a 25 to 29 kg/m2 body mass index (BMI), neck pain with arm radiation for more than 6 months, unilateral radiculopathy symptoms, and cervical muscle power not less than grade four according to manual muscle test, with moderate to severe neck disability score according to the Neck Disability Index (NDI) [7] and pain severity above 5 according to the visual analogue scale for pain (VAS-P) [8]. The subjects’ exclusion criteria included any cervical disc prolapse, spondylolisthesis, subluxation or fracture, pregnant females, patients with systemic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis or neoplastic lesions, patients with vertebrobasilar insufficiency, any previous surgery in the cervical region, and any further neurological diseases, deformities of the spine or upper extremity or disorders of the musculoskeletal system, and overweight patients to avoid situations where load could aggravate symptoms.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated through G*POWER statistical software (version 3.1.9.2). Using a = 0.05, power 80%, and effect size = 0.46 (F tests, mixed design, repeated measures, and within-between interaction), the required sample size for this study was 40 subjects.

Outcome measures

A physiotherapist with over 10 years of experience in the neurology field completed pre and post-evaluations and was blinded to patient allocation.

Neck Disability Index (NDI)

The NDI is considered a valid measurement for neck pain and disabilities in patients with cervical disorders and CR [7] and can be used to monitor the patient’s prognosis during rehabilitation [9]. NDI comprises ten categories as follows: pain intensity, personal care, lifting, reading, headaches, concentration, work, driving, sleeping, and recreation, with a score (0:5) for every cat egory, fifty points is the maximum score, with interpretation scoring of 10-28% (5-14 points) a mild disability; 30:48% is moderate; 50:68% is severe; 72% or above is complete.

The Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire

The Quick DASH is a condensed version of the original DASH scale, it is a 5-point scale that includes 11 items, with greater disability and severity levels represented by higher scores, and a score of 0 indicating no disability while 100 indicates most severe disability [10].

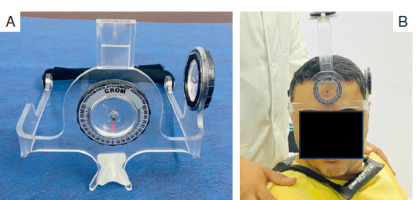

Cervical range of motion (CROM) goniometer device measurements

The CROM goniometer device is an inclinometer system for measuring the active ROM of the cervical spine [11]. From a sitting position, With the patient’s head in a neutral position, the device’s anterior inferior edge was put along the curve of the eyebrow, with the CROM device’s inferior posterior edge at the same level. The patient performed cervical rotation as much as he could, and the movement angle of the cervical spine was recorded as the difference between the pointer value and the post-neck movement value (Figure 2).

Visual analogue scale for pain (VAS-P)

The VAS-P is valid and reliable for measuring pain intensity on a 10 cm horizontal straight line of fixed length, as the left end of the line presents the highest pain level, which is 10, while the right end presents the minimum pain level of 0. Then the patient is asked to put a mark, on the line indicating the level of pain sensation [8].

Intervention

The study group received selected physical therapy treatment, as did the control group, combined with the gross MFR composed of a gross stretch of posterior cervical musculature that was applied first, then the (arm pull) gross stretch of the upper quarter. The mechanism of gross MFR includes removing any movement constriction, releasing tension, improving circulation, neuromuscular efficiency, and preservation of muscular length. The posterior cervical musculature gross stretch was applied by a physiotherapist with experience in manual therapy techniques and neurological intervention of more than 10 years. With the patient lying in a supine position, the thumbs of the therapist were placed on the patient’s neck musculature laterally, with the therapist’s hand at the occiput base and spreading to the upper part of the patient’s head. The other hand is placed on the upper thoracic spine, and the gross stretch is performed by stretching upward at the occiput base and downward at the upper thoracic spine (Figure 3). The stretch was maintained for 90 seconds, released, then repeated with more traction and extension. The repetitions were performed until reaching the end feel, which was referred to as a barrier of tissue resistance. Next, the second gross stretch of the upper quarter (Arm pull), was applied from a supine lying position as follows: The arm pull stretch was performed parallel to the floor in a straight line, so the starting position of the upper limb of the patient was in a neutral position with the patient’s elbow in extension, and the therapist grasped the patient’s hand, then slight traction was applied, and maintained the stretch till the release of fibres was felt, then, the traction increased gradually. This procedure was repeated until reaching the end feel, with gradual supination during the stretch until feeling the restricted point, then the traction was held with more supination, and if complete supination was not achievable, the forearm was moved to a neutral position. From this position, stretching of the palm was done as the therapist’s hand was placed on the thenar eminence and the other on the hypothenar eminence. The patient’s arm was then externally rotated till the feeling of restriction, and maintained at this position, then released, and repeated (Figure 4). Both types of MFR were repeated 3-5 times with 60 seconds of rest in between [5, 12].

Figure 3

Posterior cervical musculature gross stretch was applied from a supine lying position A - The starting position as the thumbs of the therapist on the patient’s neck laterally, with the therapist’s hand at the occiput base and spreading to the upper part of the patient’s head. The other hand is placed on the upper thoracic spine B - The gross stretch is performed by stretching upward at the occiput base and downward at the upper thoracic spine

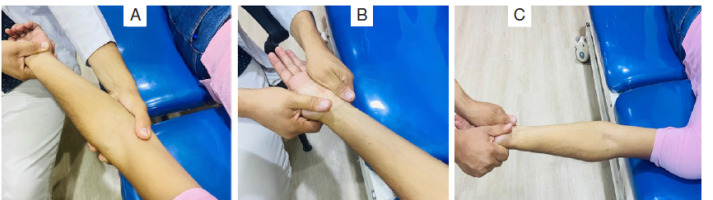

Figure 4

Gross stretch of the upper quarter (arm pull): A - the starting position of the upper limb of in a neutral position with the elbow in extension, and slight traction was applied, B - stretching of the palm with the therapist’s hand on the thenar eminence and the other on the hypothenar eminence, C - the patient’s arm was then externally rotated till the feeling of restriction and maintained at this position

The patient in the study group also received a selected physical therapy program as in the control group, which was composed of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) that was applied for 15 minutes with a frequency ranging from 80-120 Hz with the intensity increased by 10 as per the tolerance of the patient with the two electrodes placed along with the referred pain, Then hot packs were applied for 15 minutes on the posterior aspect of the neck and shoulders as the patient was in a prone lying position, followed by exercises according to the guidelines of the first phase with patient education and instructions about every exercise. Phase two included muscle activation: (1) pectoralis muscle flexibility stretching exercise as every stretch included a 30 second stretch followed by a 30-second relaxation period with 5 repetitions, (2) static neck extension exercises with maximum resistance for extension without the aggravation of neck pain or radiculopathy This was maintained for 10 seconds, 10 times per set, with two sets per session with 30 seconds of relaxation between sets [13].

Statistical analysis

Subject characteristics were compared between groups by unpaired f-test for numerical data and chi-squared test for categorical data. Variables were investigated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and for homogeneity by Levene’s test. An unpaired f-test was performed to compare cervical rotation between groups, and a paired f-test was performed for comparison within a group. VAS, quick DASH, and NDI were compared between groups by the Mann-Whitney U test and compared within groups using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. For all statistical tests, the alpha level was set at 0.05. All statistical analysis was conducted with the statistical package for social studies (SPSS) version 25 for Windows (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Subject characteristics

Subject characteristics are summarised in Table 1. No significant difference between groups in demographic data was identified (p > 0.05).

Table 1

Comparison of subject characteristics between study and control groups

Effect of treatment on cervical rotation, VAS, quick DASH, and NDI

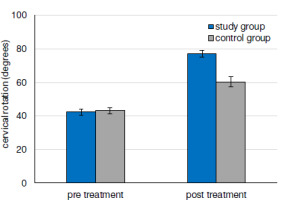

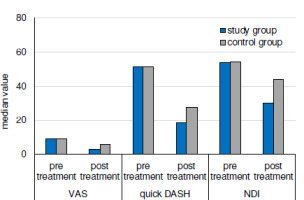

Comparison between pre and post-treatments revealed a significant decrease in VAS, quick DASH, and NDI post-treatment in both groups compared with pre-treatment (p = 0.001). There was a significant increase in rotational CROM measurements post-treatment in both groups compared to pre-treatment (p = 0.001) (Tables 2-3, Figures 5-6).

Table 2

Mean cervical rotation pre and post-treatment of both groups

Table 3

Median values of VAS, quick DASH, and NDI pre- and post-treatment of both groups

Comparison between groups revealed no significant differences between groups pre-treatment in rotational CROM measurements (p = 0.22), VAS scores (p = 0.39), quick DASH scores (p = 0.81), and the NDI (p = 0.56). There was a significant increase in rotational CROM measurements in the study group compared to the control group post-treatment (p = 0.001). There was a significant decrease in VAS, quick DASH, and NDI of the study group post-treatment compared with that of the control group (p = 0.001) (Tables 2-3, Figures 5-6).

Discussion

This study examined the treatment of patients with unilateral CR with a selected, designed program, while the study group also received gross MFR therapy in the form of a gross stretch of the cervical posterior musculature and upper quarter (arm pull). These findings support the alternative hypothesis, that cervical gross MFR will produce changes in function and pain in CR. The outcomes showed that the study group had a higher statistically significant reduction in NDI, Quick DASH scores, and pain levels with improvements in CROM scores.

In the current study, the overall situation of the patients with CR improved by the use of MFR, which was in agreement with Shah and Bhalara [4], who stated that the gross MFR application for approximately 90 seconds is required for the fascial network to respond to the slow, gentle pressure applied to it. Therefore, gross MFR is a safe and gentle treatment resulting in the removal of restrictions that prevent free movement, as a result, it helps to restore motion, relieves and eliminates soft tissue pain, also improves blood flow to eliminate fibrous compression. This leads to improvement in the tissue texture and tension and modifies imbalances of the muscles. However, the mechanism of gross MFR has demonstrated in the fascia, a connective tissue alongside muscles, joints, and bone, the reorganisation of the tissue, hence eliminating any physical restrictions and unconscious holding, resulting in fascial realigning, relaxing, and lengthening. This occurred as a result of dynamic connective tissue changes [4]. A study by Sambyal et al. [12], found that the arm pull technique of MFR decreases the disability of CR, allowing patients with CR to regain their functional activities.

Research by Gauns and Gurudut [5] examined the influence of gross MFR of the upper extremity and cervical spine in the study group while the other group received conventional physiotherapy using hot moist pack, TENS, stretching, and strengthening exercises in patients suffering from mechanical neck pain that referred to the unilateral upper extremity. The outcomes demonstrated that both groups showed a decrease in pain intensity, an increase in CROM, and functional levels, with a significant improvement in the Gross MFR group, after 5-6 sessions. Therefore, the gross MFR of the upper limb is considered an important technique for the treatment of cervical pain that refers to the upper extremity.

Previous research has studied the effect of different manual therapy techniques for CR as Thoracic Spine Thrust Manipulation and Soft Tissue Mobilization, including interventions to promote neural mechano-sensitivity and to increase the muscle power of both scapulothoracic muscles and neck flexors [14]. A combination of thrust and non-thrust mobilisation/manipulation and cervical traction [15] revealed improvement in pain and function in patients with CR; however, Tozzi et al. [16] studied the influence of fascial release on non-specific cervical or lumbar pain, as gross MFR promoted the release of fascial restrictions, regaining the tissue elasticity and reducing pain.

Several previous studies evaluating the role of cervical and upper extremity gross MFR on both function and pain in mechanical cervical pain with upper limb radiculopathy proved that the gross MFR is effective in reducing mechanical neck pain and in increasing cervical functional abilities [17]. The results showed a significant reduction in VAS-P and an improvement in DASH scores [3]. Therefore, the MFR is considered an approach that emphasises removing movement restrictions and increasing circulation [18]. Previous studies showed the effects of gross MFR in improving patients with low back pain with radiculopathy [19]. Basumatary et al. [20] stated that MFR had a great effect as a fundamental method of intervention to improve mobility and reduce tightness.

In agreement with a previous study, the conventional selected exercise therapy in our study had a significant role in improving cervical function and ROM and pain reduction. In patients with CR, flexibility and stretching exercises can preserve active ROM and normal function of the neck, prevent scarring or adhesion formation, and avoid repetitive microtrauma of the neck. The improvement of cervical function could be reached by regaining the normal muscle balance through muscle strength exercises and stretching the tight muscles, which could relieve pain and improve cervical function [21, 22]. A previous study demonstrated improved soft tissue extensibility and stretching of the upper quarter pectoralis muscle in CR leads to decreased CR symptoms [14]. However, static neck exercises had a significant impact on reducing cervical pain and disability among patients with cervical pain, including radicular symptoms, as they improve the function of neck muscles without stimulating pain-sensitive constructions such as cervical joints, tendons, or ligaments [23].

Selected intervention methods, such as heat application, stretching exercises, and TENS, are considered the most numerous therapies in CR patients besides surgical intervention, which aims to prevent and reduce cervical muscle fatigue, which is susceptible to decreasing both the individual postural stability and the proprioception of the neck muscles [24]. Besides the application of TENS that was used in the present study, we considered a modality to relieve pain for radiculopathy, as the effect was demonstrated in previous research that studies the combination of manual therapy techniques with electrotherapy using the TENS modality in the treatment of CR [3]. The limitations of the current study included the lack of long-term follow-up in patients with CR and the lack of instrumentation for measurement of tissue extensibility. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies investigate the long-term effect of MFR in patients with CR, assess the difference in sensory loss or motor symptoms after MFR in patients with CR, and investigate the effects of gross MFR versus cervical stretching exercises.