Introduction

Soccer is one of the most popular competitive team sports in the world and is favoured by people of all ages and genders. Nowadays, the number of women soccer players has increased significantly, with previous studies reporting an increase of 7.5% in one year. As such, there are 1.2 million registered women soccer players worldwide [1].

Soccer players and coaches find it difficult to improve their competitive performance through physical [2], psychological, and technical aspects [3]. Data from previous studies show that several factors make a major contribution to players achieving a high performance in soccer [4-6]. As a result, verbal encouragement is recommended for coaches as a stimulus in training sessions [7-9]. Verbal encouragement can be interpreted as positive feedback from the coach to players throughout training sessions [10]. Feedback has several types, including visual, tactical, and verbal encouragement, which complement each other. In theory, the word “feedback” means a response to an action, while “encourage” means encouragement, so verbal encouragement can be interpreted as verbal feedback from a coach to their players [9]. Several previous studies reported that verbal encouragement is an effective training tool for improving mood quality [11], enjoyment [12], technique [13], and physical parameters [14]. In addition, Pacholek and Zemková [15] stated that verbal encouragement increases physical fitness gradually and consistently. Although the application of verbal encouragement has increased in popularity and is often found in training conditions [16], there are limited studies on combining it with sided games.

Sided games are divided into small, medium, and large formats and are a very popular training method in soccer [17-19]. According to the literature, sided games are modified games that use a smaller field size [20], shorter game time, and fewer players than normal soccer rules [21, 22]. In sided games, players are required to perform defensive and offensive actions in order to score goals [23], which promotes many movement activities that players must carry out during competition [3, 24]. A recent study noted that verbal encouragement during sided games can improve aerobic performance, mood state, satisfaction, and subjective effort of soccer players [25]. In addition, Khayati et al. [26] emphasised that coaches should integrate verbal encouragement into sided games in basketball training as it can optimise players’ psychological and physiological development.

To the best of our knowledge, only a few previous studies have analysed the influence of verbal encouragement during large-sided games [25-27]. In addition, little research has investigated verbal encouragement during large-sided games to improve physical, psychological, and technical performance among female soccer players, and the impacts are unclear. Thus, our study aimed to evaluate the effects of verbal encouragement during large-sided games on physical, psychological, and technical performance among female soccer players. In this regard, we hypothesised that female soccer players receiving verbal encouragement during largesided games would experience higher physical, psychological, and technical performance improvement than a control (non-verbal encouragement).

Material and methods

Participants

G*Power (version 3.1.9.2; Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) conducted a priori sample size analysis using an E-test with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for within-between interaction analysis (effect size f = 0.30, power 1-β err prob = 0.90, and a err prob = 0.05). The calculation results showed that the minimum number of participants (sample) was 32.

Thirty-two female soccer players were recruited from the Faculty of Sport and Health Science, Univer- sitas Negeri Surabaya (Indonesia) because they were appropriate or aligned with the objectives of this research. The inclusion criteria were 100% attendance during training, no injuries in the past year, at least one-year of large-sided games training experience, and elite-level female soccer players. Exclusion criteria were participating in national or international level competition during the period of the study and no parental permission. All participants were required to sign a written consent form to indicate their willingness to participate in the study. In addition, they were given information about the rules, study design, benefits, and risks. Participants were assigned to experimental (verbal encouragement during large-sided games, n = 16) and control (n = 16) groups.

Table 1 shows age, height, weight, body mass index, and sided game experience.

Table 1

Demographic and morphological characteristics of the participants

Measures

The physical performance tests were validated for a target sample of female soccer players.

Physical

20 m sprint test

The 20 m sprint test measured running speed. Participants stood on the starting line and, after the instruction “Go”, ran as fast as possible towards the finish line. The length of the track from the starting line to the finish line was 20 m. The sprint time was recorded using an infrared photoelectric cell connected to a timing system (Saint Wien Digital Timer Press H5K, Taipei Hsien, Taiwan) [28]. Players were given two attempts, and the shortest time was used for statistical analysis [29].

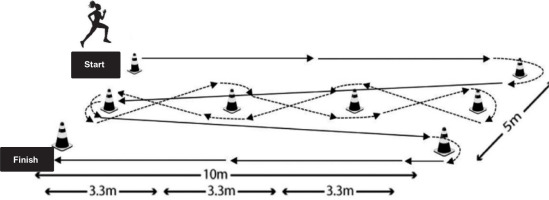

The Illinois Agility Test

The IAT measured the level of agility among players [24]. All players stood on the starting line, and after the researcher’s command of “Go” the player ran as fast as possible in a zig-zag manner around the field towards the finish line (Figure 1). Each player had two attempts chances, with the fastest time recorded for data processing.

Multistage fitness test

The multistage fitness test (MFT) can measure maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) in soccer players [30]. The players stood at cone A, and after an audible “beep”, all players ran towards cone B. The activity was carried out continuously until a player was unable to run or follow the rhythm of the “beep”. The number of running levels (back and forth) was converted to VO2 max (ml/kg/min) [31].

Psychological

Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale

Previous studies revealed that PACES can measure the level of enjoyment during physical activity [4]. The questionnaire consists of 18 items, with 11 indicating negative feelings and seven indicating positive feelings. For example, “How do you feel about doing this physical activity?” A seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (I like) to 7 (I hate) was used to answer the questions. The total score was calculated for each individual, with higher scores signifying more enjoyment [26].

Satisfaction Scale for Athlete

The SSA uses 16 questions from three dimensions, including satisfaction with the coach (six questions items), satisfaction with team performance (five items), and satisfaction with teammates (five items) [25]. For example, “Are you satisfied with the training program implemented by the coach?” A Likert scale was used to rank the answers from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 7 (extremely satisfied).

Execution skills

In order to measure the execution skills response of the players, the game was recorded by a digital camera (Samsung NX300) placed outside the field [3]. Based on previous studies [32], three expert analysts assessed technical performance related to several execution skill indicators, including failed to pass, successful passing, failed to tackle, successful tackles, failed to shoot, and successful shots.

Study design and procedures

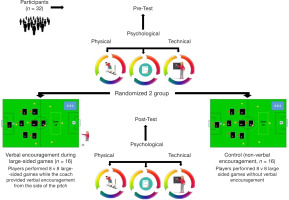

The study took place over eight weeks between August and September 2024. In the first week, we implemented a pre-test protocol involving physical performance tests (20 m sprint test, IAT, and MFT) on Monday, psychological tests (PACES and SSA) on Wednesday, and technical tests (execution skills) on Friday. All activities were carried out from 07:00-10:00 at the Surabaya State University Gymnasium and were directly supervised by the research team. In the second week, the experimental group received verbal encouragement during large-sided games, while the control group only carried out routine soccer training (Figure 2). After eight weeks, all participants took the post-test between 07:00 and 10:00, which involved all physical, psychological, and technical performance drills.

Training protocol

The programme for verbal encouragement started with a five-minute warm-up and continued during large-sided games (8 v 8), with three sessions per week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday). In each session, participants undertook three 15-minute rounds, with a two-minute recovery break (Table 2), and ended the activity with a five-minute cool-down. The experimental and control groups consisted of teams A and B, with each team comprising one goalkeeper, three defenders, three midfielders, and one striker. The largesided games used a medium pitch format, with a relative pitch area of 157.5 m2. If the ball went out of play, the game would restart from the goalkeeper. During the games, the coach was on the sidelines to provide positive verbal encouragement (e.g., “Come on” and “Spirit”) to each player. Encouragement was also given during the break. The coach who ran the programme (BP) had more than five years of experience in soccer training, while the coach in the control group (DL) had six years. In the control group, participants only carried out daily activities such as basic technique drills and technique execution in fixed situations. Each exercise was done for 15 min, with two minutes for rest.

Table 2

Verbal encouragement during the eight-week large-sided games programme

Statistical analysis

We presented descriptive statistics in the form of mean ± standard deviation. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test (p > 0.05). The reliability of each variable is presented as an ICC. An independent samples t-test assessed the effects of verbal encouragement during large-sided games and under control conditions before the experiment (pre-test).

A two-way repeated measures ANOVA evaluated the effects of time factors (pre- vs post-test) and group factors (verbal encouragement during large-sided games vs control) on physical (20 m sprint Test, IAT, and MFT), psychological (PACES and SSA), and technical (execution skills) aspects. In addition, the interaction factor (time vs group) was tested. To identify changes within each group over time and significant interaction effects, we conducted post hoc tests using the Bonfer- roni method. The effect size (ES) was calculated using Cohen’s d and marked as small (0.20), medium (0.50), or large (0.80) [33]. A Student’s t-test compared pre and post-test data for each group. Moreover, the delta percentage test (%Δ) was calculated [(post-test - pretest / pre-test) x 100]. The significance level was set at p < 0.05, and all statistical analyses employed Jamovi version 2.3.28 (The Jamovi Project, Sydney, Australia).

Results

Table 3 shows the results of the reliability test (ICC = 0.80-0.96) and the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality (p > 0.05). The independent samples t-test showed no significant difference between the two groups before the experimental phase (Table 4).

Table 3

Reliability and normality tests

[i] 20mST - 20 m sprint test IAT - Illinois Agility Test MFT - multistage fitness test PACES-NF - physical activity enjoyment scale - negative feelings PACES-PF - physical activity enjoyment scale - positive feelings SSfA-SwC - satisfaction scale for athlete-satisfaction with coach SSfA-SwTP - satisfaction scale for athlete-satisfaction with team performance SSfA-SwT - satisfaction scale for athlete-satisfaction with teammates ICC - intra-class correlation coefficient SW - Shapiro-Wilk’s VE during LSGs - verbal encouragement during large-sided games non-VE - non-verbal encouragement

Table 4

Comparison of student test indicators in the group using verbal encouragement during the big side game and the control group before the experiment (pre-test)

[ii] VE during LSGs - verbal encouragement during large-sided games PACES-NF - Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale-negative feelings PACES-PF - Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale-positive feelings SSfA-SwC - Satisfaction Scale for Athlete-Satisfaction with coach SSfA-SwTP - Satisfaction Scale for Athlete-satisfaction with team performance SSfA-SwT - Satisfaction Scale for Athlete-satisfaction with teammates NS - non-significant differences

Effects of verbal encouragement during large-sided games (non-verbal encouragement) on physical performance

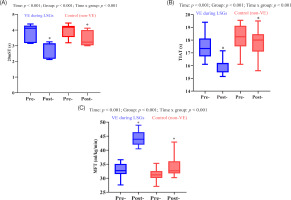

The results of the two-way repeated measures ANOVA (Figure 3) showed that there was a time effect (pre vs post-test) on physical variables related to the 20 m sprint tests (F(1.30) = 43.93; p < 0.001), the IAT (F(1.30) = 130.3; p < 0.001), and MFT (F(1.30) = 157.7; p < 0.001). In addition, there was a significant group effect of verbal encouragement during large-sided games vs control in the 20 m sprint test (F(1.30) = 6.49; p = 0.016), the IAT (F(1.30) = 11.9; p = 0.002), and MFT (Fa.30) = 47.9; p < 0.001). The two-way repeated ANOVA showed an interaction effect (time vs group) in the 20 m sprint test (F(1.30) = 46.0; p < 0.001), IAT (F1.30) = 34.1; p < 0.001), and MFT (F(1.30) = 47.0; p < 0.001). Subsequent post hoc analyses demonstrated distinct outcomes for each group.

Figure 3

Effects of verbal encouragement during large-sided games (VE during LSGs) and control [non-verbal encouragement (VE)] on (A) 20 m sprint tests (20mST), (B) the Illinois Agility Test (TIAT), (C) and multistage fitness fest (MFT). Statistical differences at p < 0.001

The Student’s t-test (Figure 3) showed significant differences between pre and post-test in the 20 m sprint tests (Δ = -26.5; d = 1.42), IAT (Δ = -7.5; d = 3.36) and MFT (Δ = +35.4; d = -2.81) in the verbal encouragement during large-sided games, and in the 20-m sprint tests (Δ = -13.8, d = 1.28), IAT (Δ = -2.7; d = 0.92), and MFT (Δ = -2.7; d = 0.91). These results indicate that the improvement was greater in the verbal encouragement during the large-sided games group than in the control.

Effects of verbal encouragement during large-sided games and control on psychological performance

The results of the two-way repeated ANOVA analysis (Table 5) showed a significant effect of time (pre- vs post-test) on psychological variables related to PACES negative feelings (Fp.30) = 174.8; p < 0.001) and positive feelings (F(1.30) = 254.3; p < 0.001), SSA satisfaction with the coach (F(1.30) = 170; p < 0.001), satisfaction with team performance (F(i.30) = 166.7; p < 0.001), and satisfaction with teammates (F(1.30) = 64.1; p < 0.001). We also found group effects of verbal encouragement during largesided games vs control on PACES negative feelings (F(1.30) = 39.8; p < 0.001), SSA satisfaction with the coach (F(1.30) = 16.5; p < 0.001), satisfaction with team performance (F(1.30) = 8.71; p = 0.006), and satisfaction with teammates (F(1.30) = 13.2; p = 0.001), but not on PACES positive feelings (F(1.30) = 0.160; p = 0.692). Finally, we observed interaction effects (time vs group) on PACES negative (F(1.30) = 51.2; p < 0.001) and positive feelings (F(1.30) = 93.8; p < 0.001), SSA satisfaction with the coach (F(1.30) = 103; p < 0.001), satisfaction with team performance (F(1.30) = 88.9; p < 0.001), and satisfaction with teammates (F(1.30) = 27.8; p < 0.001). Subsequent post hoc analyses demonstrated distinct outcomes for each group.

Table 5

Comparison of psychological and technical performance in pre- and post-test between verbal encouragement during large-sided games and control (non-verbal encouragement) groups. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD)

[i] VE during LSGs - verbal encouragement during large-sided games, non-VE - non-verbal encouragement, PACES-NF - Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale-negative feelings, PACES-PF - Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale-positive feelings, SSfA-SwC - Satisfaction Scale for Athlete-Satisfaction with coach, SSfA-SwTP - Satisfaction Scale for Athlete-satisfaction with team performance, SSfA-SwT - Satisfaction Scale for Athlete-satisfaction with teammates, Δ - percentage change, NS - not significant * indicates significant differences in time, interaction and group factors in the two-way repeated analysis of variance

Student’s f-test (Table 5) showed significant differences between pre-, and post-test on Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale: negative feelings (Δ = +51.8; d = -3.40), and positive feelings (Δ = +89.1; d = -4.51), Satisfaction Scale for Athlete: satisfaction with coach (Δ = +88.6; d = -3.11), satisfaction with team performance (Δ = +124.8; d = -2.87), satisfaction with teammates (Δ = +74.8; d = -1.77) in the verbal encouragement during large sided games group, and in the control group on Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale: negative feelings (Δ = +15.9; d = -1.15), and positive feelings (Δ = +16.1; d = -1.11), Satisfaction Scale for Athlete: satisfaction with coach (Δ = +8.7; d = -0.98), satisfaction with team performance (Δ = +13.9; d = -1.93), satisfaction with teammates (Δ = +9.7; d = -0.96). These results indicate that verbal encouragement during large sided games shows a higher increase than control.

Effects of verbal encouragement during large-sided games and control on technical performance

The two-way repeated ANOVA (Table 5) showed a significant effect of time (pre vs post-test) on the technical variables failed to pass (F(1.30) = 77.82;p < 0.001), successful passing (F(1.30) = 95.4; p < 0.001), failed to tackle (F(1.30) = 41.5; p < 0.001), successful tackles (F(1.30) = 58.60; p < 0.001), failed to shoot (F(1.30) = 97.03; p < 0.001), and successful shots (F(1.30) = 111.67; p < 0.001). In addition, we observed a group effect of verbal encouragement during large-sided games vs control on failed to pass (F(1.30) = 84.1; p < 0.001), successful passes (F(1.30) = 120; p < 0.001), failed to tackle (F(1.30) = 31.2; p < 0.001), failed to shoot (F(1.30) = 4.27; p = 0.001), and successful shots (F(1.30) = 5.24; p = 0.029), but not successful tackles (F(1.30) = 0.634; p = 0.432). Finally, there was an interaction (time vs group) on the variables failed to pass (F(1.30) = 9.09; p = 0.005), successful passing (F(1.30) = 43.5; p < 0.001), failed to tackle (F(1.30) = 93.5; p < 0.001), successful tackles (F(1.30) = 8.91; p = 0.006), and successful shots (F(1.30) = 12.5; p = 0.001), but we did not find any effect on failed to shoot (F(1.30) = 0.615; p = 0.439). Subsequent post hoc analyses demonstrated distinct outcomes for each group.

Student’s f-test (Table 5) showed significant differences between pre and post-test in failed to pass (Δ = -38.5; d = 2.54), successful pass (Δ = +55.9; d = -2.85), failed to tackle (Δ = -40.0; d = 3.03), successful tackles (Δ = +36.6; d = -1.88), failed to shoot (Δ = -28; d = +2.0), and successful shots (Δ = +80.4; d = -1.65) in the experimental group, and in failed to pass (Δ = -16.1; d = 0.89), successful pass (Δ = +15.4; d = -0.57), failed to tackle (Δ = +13.8; d = -0.53), successful tackles (Δ = +14.1; d = -0.82), failed to shoot (Δ = -29.1; d = +1.70), and successful shots (Δ = +96.2; d = -1.45) in the control. The data demonstrated that the experimental group improved more than the control.

Discussion

The study revealed the effects of verbal encouragement during large-sided games on physical, psychological, and technical aspects among female soccer players. The results confirmed our initial hypothesis by showing that verbal encouragement during largesided games had more effect than the control conditions on increasing physical performance in the 20 m sprint test, IAT, and MFT in female soccer players. Previous studies showed that positive verbal encouragement from the coach (e.g., “Go” or “Again”) was a good stimulus for players during large-sided games sessions and increased physical fitness more than the control conditions in female adolescents in Tunisia [27].

Modern training processes not only rely on a training program, but verbal feedback from a coach can be a positive strategy to promote physical fitness in team sports [34]. Indeed, Romdhani et al. [25] recommended integrating verbal encouragement into sided games in an effort to change the aerobic performance of soccer players from poor to excellent. Another study also showed that verbal encouragement improved the speed, agility, and endurance of 24 young soccer players [31], while others have found improvements in physical abilities after integrating verbal encouragement during training sessions [35].

In accordance with our second hypothesis, the evidence showed that verbal encouragement during largesided games increased psychological parameters (e.g., PACES and SSA) significantly more than the control. Indeed, verbal encouragement promoted interesting training and positive feelings, including pleasure and satisfaction in carrying out training activities. A previous study supported these findings in small-sided games, with positive verbal encouragement from the coach during training gradually improving the mood [35] and satisfaction of semi-professional soccer players [25]. Similarly, Khayati et al. [26] reported increased physical enjoyment, positive mood, and higher physical activity intensity levels among basketball players following verbal encouragement from the coach in sided games training. Another study confirmed that Tunisian soccer players experienced an increase in enjoyment and mood after undergoing an integrated verbal encouragement and sided games programme [11].

The participants experienced significant increases compared to the control in technical performance after verbal encouragement for eight weeks, confirming our third hypothesis. The findings in this study are in line with previous studies reporting that technical skills development in soccer players requires sided games combined with consistent verbal encouragement [27]. Mekni et al. [34] reported similar results, with verbal encouragement during sided basketball games being more effective than the control group in improving the technical skills of basketball players. Furthermore, Jumareng et al. [31] implemented verbal encouragement during sided games to promote learning of various technical soccer skills, such as dribbling, passing, and shooting.

The uniqueness and main strength of our study was creating a different programme from previous sided games studies [36, 37]. Indeed, this study combined verbal encouragement with large-sided games to assess positive effects on physical, psychological, and technical development among female soccer players. However, there were several limitations that need to be acknowledged, including the limited number of participants involved and the use of only one gender and game format (8 vs 8). Another limitation was that we did not take into account the potential for drop-outs, so the small sample size could affect the robustness of the findings. Therefore, we suggest using a larger sample size to validate these results.

Although verbal encouragement during large-sided games was effective, factors such as gender, participant level (e.g., college players at the elite level), and duration (eight weeks) may limit generalisability. Another suggestion is to implement concrete strategies to integrate verbal encouragement during large-sided games into the training routine of male and female players. In addition, a programme should be created that only uses positive verbal encouragement for female players, and must avoid negative encouragement, such as insulting or harassing players. Indeed, negative encouragement can lead to a decline in the performance of female players, which ultimately affects match results.

Conclusions

Based on the study results, verbal encouragement during large-sided games implemented for eight weeks improved physical, psychological, and technical performance among female soccer players. The study contributes to the development of modern women’s soccer training processes, and provides important information for coaches in maintaining competitive performance among female soccer players. In addition, it offers practical recommendations for coaches, while bridging the gap between research and practice in female soccer player training. Moreover, the research makes an important contribution to helping coaches implement verbal encouragement during large-sided games in football training in the future so that they can attain much higher achievements.