Introduction

Obstacle avoidance is an indispensable function for humans to navigate their daily lives, and its neural mechanisms and control systems have been extensively studied. When avoiding obstacles, humans do not simply adjust their leg movements; rather, this process appears to involve the integration of various sensory information, including visual, somatosensory, and vestibular senses, which are then processed complexly within the central nervous system. Participants planned their obstacle avoidance by adjusting their motor parameters based on the visual perception of the obstacle’s size and distance until the last step before the obstacle [1–5]. Studies on human obstacle avoidance during walking suggest that individuals begin to prepare for obstacle avoidance as early as five steps before encountering an obstacle [6]. While numerous studies have investigated obstacle avoidance during walking using a variety of experimental paradigms, our understanding of obstacle avoidance during running is still relatively limited [7, 8].

The 3000 m steeplechase offers a fascinating opportunity to study obstacle avoidance during running. In this event, athletes must clear 28 hurdles and 7 water jumps, all set at a height of 0.914 m (men’s race) or 0.762 m (women’s race). Previous studies have investigated the kinematic and physiological characteristics of the 3000 m steeplechase [9–15]. These studies examined the characteristics of the water jump [10, 12–15] and pacing strategies [11]. Previous studies of hurdling technique have shown that runners tend to increase their step frequency in the three steps leading up to a hurdle, and this frequency typically decreases in the middle of the race compared to the initial phase [16].

Although it has been observed in races that athletes sometimes ‘get cramps’ before hurdles, this phenomenon has scarcely been studied. Participants lengthened their strides from four steps before takeoff [17] and decelerated two steps before the crossing to clear the obstacle [7]. It is assumed that athletes adjust their rhythm to clear hurdles in the most optimal manner. To investigate this, step rate is a valuable tool in race analysis [18–20]. Calculating the step rate allows for the analysis of both the individual race performance and the group of runners [20]. Weart et al. [20] investigated the stability of the step rate by video analysis and suggested that the variation in step frequency was less than 1% throughout the 3200 m run. While laboratory-based treadmill studies allow for precise control of the speed and step rate [1–6], limiting the number of studies conducted in outdoor race and training settings due to difficulties in maintaining such control, there is a relative scarcity of knowledge in long-distance running.

This study aimed to investigate the variations in step rate for obstacle avoidance during running. For this purpose, this study observed the videos of the 3000 m steeplechase. The third obstacle on the back straight was the primary focus, as it was more observable compared to those placed on curves. Furthermore, this study aimed to determine whether the step rate varies during obstacle avoidance with the number of laps completed throughout a race. The step rate was calculated from the 10 steps preceding obstacle clearance and compared among athletes and across laps. It was hypothesised that the step rate would change five steps before clearance if athletes prepare for obstacles while running similarly to walking [6]. Mohagheghi et al. [6] demonstrated that obstacle avoidance is possible even when visual input is absent for up to five steps before the obstacle, as individuals effectively utilise pre-existing visual information. Therefore, it is probable that preparation for obstacle avoidance begins at least five steps before the obstacle, even during high-speed running. Given the potential for increased fatigue in later laps [16], it was further hypothesised that the step rate would decrease in the fourth and fifth laps compared to the first lap. Previous research on the 3000 m steeplechase has reported a decrease in the step rate in the fourth and fifth laps [16].

Material and methods

Participants

Data were collected from the men’s 3000 m steeplechase races at the Kanto Intercollegiate race. The 3000 m steeplechase race consisted of seven laps. This race was part of the Kanto Intercollegiate Championships. Participation in this competition was limited to athletes who had broken the entry standards (9:25.00). Prior to the races, the research was explained to each coach, and permission to film the races was obtained. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. Performances from 75 male athletes were analysed (mean age ± SD = 20.4 ± 1.3 years). This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (2020-03).

Procedure

The 3000 m steeplechase races were recorded by video camera (CASIO, EXILIM PRO EX-F1). The sampling rate was 300 Hz and the resolution was 512 × 384 px. The third obstacle was placed on the back straight. The camera was placed to film the athletes from a sagittal view at the third hurdle on the stadium. The camera was zoomed to include 20 m before the obstacle.

Data analysis

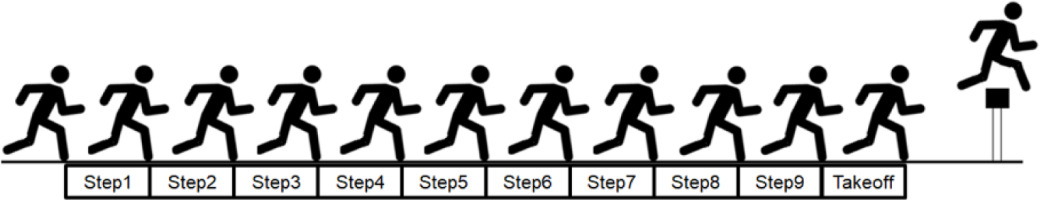

The total times for the 3000 m steeplechase races were obtained from the results documents. The analysis focused on the 10 steps immediately preceding obstacle clearance. All steps from the participants were digitalised using Kinovea (version 0.9.5). The endpoints of the segments were determined by the researchers. The step rate of the ten steps before takeoff were analysed (Figure 1). The time per step was determined from the frames captured by a high-speed camera. The step rate was the step frequency from the ten steps toe on before the hurdle to the takeoff and was determined as the inverse of the time per step (1/time per step). Comparisons of the 10-step step rate were made both across laps and among the individual steps.

Statistical analysis

The step rate of the ten steps before hurdle were subjected to two-way ANOVAs with repeated factors of lap (lap1/lap2/lap3/lap4/lap5/lap6/lap7) and step (step1/step2/step3/step4/step5/step6/step7/step8/step9/takeoff). Mauchly’s test was used to assess the assumption of sphericity. When sphericity was violated, the degrees of freedom were corrected using Green-house-Geisser’s ε. The Bonferroni correction was applied to the post-hoc comparisons. All statistical analyses were conducted using JASP (0.19.3) [21], with a significance level of p < 0.05. The effect sizes η2p for ANOVA were as follows: 0.01, small; 0.06, medium; 0.14, large [22]. The Cohen’s d effect sizes for post-hoc comparisons were as follows: 0.20, small; 0.50, medium; 0.80, large [22].

Results

Running performance

The average finishing time (min:s) was 9:16.9 ± SD 16.4. The fastest time was 8:54.9 and the slowest time was 10:07.8.

Step rate

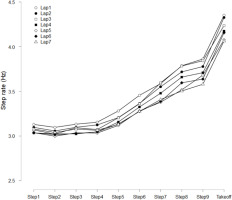

Table 1 and Figure 2 show each parameter for step rate. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was not significant for lap χ2(20) = 13.63, p = 0.85], but was significant for step χ2(44) = 702.49, p = 0.01] and the interaction between lap and step [χ2(1484) = 4129.57, p = 0.01]. For the step rate, a two-way ANOVA revealed that there was a significant interaction between lap and step [F(54,3996) = 1.97, p = 0.01, = 0.03).

Post-hoc test revealed that step rate for step1 was higher for lap1 than for lap4 (p = 0.01, d = 0.25, Table 2), lap5 (p = 0.01, d = 0.25) and lap6 (p = 0.01, d = 0.25). The step rate for step2 was higher for lap1 than for lap5 (p = 0.01, d = 0.26). The step rate for step3 was higher for lap1 than for lap4 (p = 0.04, d = 0.29), lap5 (p = 0.01, d = 0.26) and lap6 (p = 0.02, d = 0.28). The step rate for step4 was higher for lap1 than for lap4 (p = 0.01, d = 0.28), lap5 (p = 0.01, d = 0.32) and lap6 (p = 0.01, d = 0.29). The step rate for step5 was higher for lap1 than for lap5 (p = 0.02, d = 0.43) and lap7 (p = 0.03, d = 0.40).

Post-hoc analyses revealed significant differences in the step rate across different steps within each lap (ps < 0.05, Table 2). Specifically, for laps 1–6, steps 6–9 and takeoff consistently exhibited higher step rates compared to steps 1–4. Step 5 showed lower step rates than steps 7–9 and takeoff. Step 6 had a lower step rate than steps 8, 9, and takeoff. Step 7 had a lower step rate than steps 8, 9, and takeoff. Finally, steps 8 and 9 had lower step rates than takeoff. For lap 7, steps 7–9 and takeoff had higher step rates compared to steps 1, 3, 4, and 5. Steps 6–9 and takeoff had higher step rates compared to step 2. Steps 8, 9, and takeoff had higher step rates than step 6. Step 9 and takeoff had higher step rates than step 7. Finally, steps 8 and 9 had lower step rates than takeoff.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the variations in step rate during obstacle avoidance during running. Focusing on the 3000 m steeplechase race, the step rate of ten steps before takeoff was analysed. The results showed that there was a significant interaction between lap and step. In terms of step, the step rate increased from five steps before the takeoff. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have investigated obstacle avoidance during running. A previous study on obstacle avoidance during walking reported that participants began preparing to avoid obstacles five steps before reaching them [6]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that participants finish their preparations for avoiding obstacles approximately two steps before reaching them, and they tend to glance at the obstacle minimally during the final two steps [4, 5]. Consistent with findings on obstacle avoidance during walking, our results demonstrated that runners initiate preparatory adjustments to their step rate roughly five steps prior to encountering an obstacle.

Table 1

Step rate (mean, SD) in each lap and step

Few studies have shown that stride length increases before a hurdle during a full sprint [7, 17]. Using the 400-metre hurdles task, Ozaki et al. [17] found that participants adjusted their stride length from four steps before the hurdle takeoff. The athletes prepared for obstacle avoidance during sprinting in the same way as they did for walking. Mauroy et al. [7] found participants decreased their speed two strides prior to clearing the hurdle. The alterations in step parameters prior to takeoff suggest a motor adaptation designed to overcome a vertical obstacle of a specific height. It is likely that the runners in this study increased their step rate to overcome the 0.914 m obstacle.

The step rate remained consistent across multiple laps in sections far from the obstacle. These results indicate the stability of steps 1–6. Previous studies have reported that the step rate remains relatively stable regardless of whether the running is performed on a treadmill or on the road [20, 23, 24]. For example, when running at a speed that induces exhaustion within 15 min, participants exhibit a significant increase in ground contact time while the step rate remains relatively unchanged [24]. Furthermore, a study of outdoor 3200 m running reported that the change in step rate was less than 1% [20]. Step rate exhibits a high degree of individual specificity and remains relatively stable during one hour of sustained running [23]. Our findings suggest that step rate is relatively consistent, even when runners encounter obstacles that disrupt their normal running rhythm.

Table 2

Post-hoc comparisons between lap and step

It should be noted, however, that the step rate prior to obstacle avoidance decreases in the later stages of a race. In terms of laps, a significant difference was observed in steps 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. It was observed that participants decreased their step rate before encountering obstacles as the number of laps increased. A previous study suggested that the step rate at 3 steps before hurdle clearance was higher for lap1 and lap2 than for lap3, lap4, lap5, lap6, and lap7 [16]. These findings suggest that athletes may be unable to increase their step rate prior to obstacles in later stages of a race. Interestingly, no significant differences in step rate were observed among laps in steps 6 through takeoff before the hurdle. Taking these findings into account, it appears that motor preparation and control prior to preparation for obstacle avoidance becomes difficult.

Similar characteristics were observed in step rate adjustment prior to obstacles in walking and running. A possible explanation is that walking and running share common underlying physiological mechanisms. Some studies on obstacle avoidance during walking have reported that obstacle avoidance is planned by adjusting motor parameters based on visual perception [1–5]. Obstacle avoidance might be achieved not by simply adjusting leg movements, but through the integration and complex processing of multiple sensory channels, including visual, somatosensory, and vestibular cues, within the central nervous system.

This study included some limitations. First, the current study focused on an analysis of the running step rate, thereby omitting the physiological assessment of anaerobic and aerobic capacities. Future research could incorporate monitoring the physical condition through the measurement of heart rate and lactate levels. Secondly, more detailed data regarding the participants’ 3000 m steeplechase experience and current training activity levels would have been beneficial. Such data would have enabled the examination of step rate differences based on factors such as experience level in the 3000 m steeplechase and time performance.

While many studies on the 3000 m steeplechase have focused on the water jump [10, 12–15], research examining hurdling in the non-water jump is relatively limited [9, 16]. Despite having similar heights, the hurdles and water jumps in the 3000 m steeplechase require different hurdling techniques. This study observed the step rate over the 10 steps prior to the hurdle to elucidate the preparatory process for hurdle clearance. In addition, previous studies have indicated that VO2max, strength, pace variability, and jump technique are associated with improved 3000 m steeplechase performance [9, 25]. Our results demonstrated that runners initiated preparatory adjustments to their step rate approximately five steps prior to obstacle avoidance. This preparatory movement was analogous to the adjustments for obstacle avoidance observed in walking [4–6] and sprint hurdles [7, 17]. Training for the 3000 m steeplechase should not only focus on enhancing endurance-related physiological capacities but also on developing hurdle technique, particularly the preparatory phase in the five steps leading up to the hurdle.