Introduction

Cognitive functions are skills related to perception, attention, problem solving and memory functions of the human brain that help people carry out tasks, from the simplest to the most complex ones [1]. The ability to maintain attention on a desired goal, ignoring other distractions, is an important element in perception, learning, and cognition. In fact, attention is a central feature of cognitive functioning [2], which allows for the selection and processing of information through its three distinct networks responsible for controlling different attentional functions; that is, orienting, alerting, and executive control [2, 3].

Selective attention arguably has a central role in the overall improvement of attention quality of the actions a person can take to focus on specific information, while being able to diminish the attention paid to irrelevant information in the environment [4]. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by chronic difficulties in social communication and interaction, and restricted and repetitive interests and behaviours [5], has been related to selective attention difficulties in controlling which aspects of the environment to focus on, and which aspects to deliberately suppress or ignore [6]. Deficits in selective attention that stem from neuroanatomical variations within ASD create challenging interactions since children with ASD may exhibit an abnormally narrow or abnormally broad focus of attention, depending on the context [7]. This, in turn, can lead to difficulties in learning, organising thoughts and behaviours, planning daily activities, and overall quality of life for individuals with ASD [8, 9]. Thus, the development of programs aimed at recording and improving selective attention in individuals with ASD has become a focal point of research in recent years [6, 10, 11].

Children with ASD ‘think in pictures’ [12], focus their attention, and process information more easily when it is presented through visual aids compared to other forms of communication [13]. Visual aids are mainly used to improve selective attention [14], language comprehension, preparation for changes in the environment, and support for completing specific tasks [15]. Consequently, research efforts in educational settings [16, 17] indicate that visual supports can be effectively used to assist students with ASD who face difficulties in processing, understanding, and utilising information received from their environment through verbal communication [18].

Visual supports can be categorised as either ‘low-tech’, such as symbols, photographs, objects, images or written words, or ‘high-tech’, which utilise electronic devices. These supports are often cost-effective, versatile, portable, suitable for use in various settings (e.g., classrooms, homes), and beneficial for a wide age range, providing a tangible and consistent method of communication, in contrast to the transient and variable nature of spoken language [13]. Cohen and Demchak [16], in their systematic review to examine the effectiveness of visual supports such as picture schedules and visual cues in promoting task independence for students with ASD, indicate that visual supports significantly enhance task performance by improving selective attention, reducing the reliance on verbal prompts and fostering autonomy. Therefore, they are effective in helping individuals with ASD focus on relevant stimuli, process information more efficiently, and complete tasks independently [16].

Over the past decade, traditional visual supports have served as the foundation for transferring visual material into electronic formats. Applications have transformed the conceptual elements they contain into an innovative digital form, making them more accessible and engaging through mobile applications [19]. Mobile apps can offer additional features compared to traditional visual supports through the increasingly developing technology and have gained more use in the last decade [20]. Research evidence demonstrates the crucial role of mobile applications in the learning process and cognitive development of children with ASD even with minimal guidance, helping children with ASD to express needs and emotions and enhance their autonomy in primary care and education settings [21, 22].

A widely used cognitive assessment tool through mobile apps is the cancellation test, whose popularity stems from its ability to assess attention in a simple way and its effectiveness is highlighted in assessing visual attention across various neurodevelopmental and other disorders, including ASD [23], attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder [24], learning disabilities [25] and Alzheimer’s disease [26]. According to Cas-caes et al. [27], automated cancellation tests provide valuable information about children’s visual exploration strategies, aligning with traditional assessment outcomes and highlighting their potential for broader application in both research and practical contexts. However, most research to date has primarily centred on adults, with relatively few studies focusing specifically on children [27–29].

Furthermore, most research has taken place in educational or school settings, ignoring recreation environments and activities that play an important role in the development of children with ASD [11, 27]. Climbing in particular – either rock or indoor – constitutes one of the most representative activities in recreation settings for all participants with and without disabilities [30, 31]. One distinctive feature of climbing is its inclusivity, allowing individuals of nearly any age, physical skill level, or cognitive ability to engage at their own skill level while participating alongside others at different levels [32], while also promoting both fine and gross motor skill development and offering cardiovascular benefits [31] and opportunities for social interaction [35] of climbers who are typically conscientious, intrinsically motivated, and task-oriented individuals [36].

It is worth noting that selective attention may be efficient and beneficial in some tasks, such as navigating an indoor climbing route, but may be maladaptive in others, such as failing to recognise a threatening stimulus like an angry face [37]. Individuals with ASD who exhibit excessive selective attention may struggle in complex social interactions, which require not only focusing on climbing holds or footholds but also sharing experiences with others.

Nevertheless, climbing is considered an ideal recreational activity for individuals with ASD due to its concrete and straightforward rules, as each climb culminates in the achievement of a specific goal [35]. Indoor climbing typically involves three main rules, that is, ascend the wall, follow the designated routes, and release the holds at the end to be lowered down [35]. In most established climbing gyms worldwide, routes are clearly marked with distinct coloured tape, with each hold along a route featuring a strip of tape in a specific colour extending from its base, making the route easy to identify. These routes are carefully designed by professional route setters or experienced climbers and are categorised by varying levels of difficulty. This setup allows participants to select routes that match their skill level and progressively challenge themselves [38]. Following designated routes promotes proper climbing techniques and increases physical effort. Walls typically feature multiple routes side by side, each differentiated by its unique tape colour. As climbers follow a route, each hold acts as a clear prompt, or discriminative stimulus, for the action of reaching and grasping. The coloured tape further serves as a conditional cue, guiding the climber to interact only with climbing holds or footholds marked by the specified colour. This structured system supports skill development while offering a clear and engaging activity [35].

Research has investigated the cognitive benefits associated with climbing, including its impact on concentration and attention. Garrido-Palomino et al. [39] explored the relationship between attention and the self-reported climbing proficiency of experienced climbers, highlighting the significance of attention as a key factor in climbing performance of advanced climbers who demonstrated heightened attention particularly in on-sight lead climbing. Furthermore, Whitaker et al. [40] investigated the impact of climbers’ expertise on their ability to perceive action capabilities, recall visual details of holds, and remember planned and executed movements. Their results indicated that greater climbing expertise is linked to improved performance in both perceptual and cognitive tasks.

As for neurodevelopmental conditions, research that focused on children with attention-deficit/hyper activity disorder (ADHD) found that engaging in rock climbing at light to moderate intensity was associated with improvements in attention and behaviour, suggesting that climbing can be an effective intervention to enhance attention in children with ADHD [41]. Ko-karidas et al. [32] examined the impact of a 12-week indoor climbing program on handgrip strength and traverse speed in children with and without ASD. The findings indicated improvements in both physical skills, suggesting that climbing can be a beneficial recreational activity for enhancing physical abilities in children with ASD.

While direct scientific studies specifically examining the effects of climbing on attention or cognitive function in children with autism spectrum disorder are limited, climbing activities are recognised for their potential benefits in these areas. Climbing requires focus, problem-solving, and motor planning, which can enhance the cognitive functions, attention [40], and learning of children with ASD, as they follow specific routes, as a result of attention and cognitive processing improvements [42]. Climbing also provides proprioceptive and vestibular input, which can help regulate sensory processing and improve concentration in children with ASD. Engaging in structured physical activities like climbing has been associated with enhanced executive functions, including working memory and cognitive flexibility, which are crucial for attention and concentration [6].

Overall, while more targeted research is needed, existing evidence suggests that climbing activities may positively influence concentration, cognitive function, and selective attention in children with ASD. So far, only the study by Oriel et al. [43] has examined the social validity of a rock climbing program as a community-based activity for 10 adolescents with ASD and its effectiveness on attention. Nevertheless, while all parents agreed that rock climbing was a good activity to address participation of their children with ASD, the small sample size of this pilot study yielded no statistically significant results in attention test scores [43]. Reviewing the literature, no other research efforts have been found that are similar to Oriel et al.’s [43] study. Thus, this study intends to draw more decisive findings using a larger sample and a longer intervention period.

Material and methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 34 participants with ASD (23 males and 11 females) ranging in age from 7 to 13 years (M = 9.62 years, SD = 1.55). Each participant had been formerly diagnosed as having ASD (level 1 with no intellectual disability or other disorders present) using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition, Text Revision (5).

The participants were recruited through a flyer sent to local schools for participation in the indoor climbing program, with prior consent provided by primary education authorities. The recruitment flyer with listing details of the indoor climbing activity was also provided to families through email, and parents who were interested in receiving more information contacted the primary researcher of this study directly.

Following recruitment, 42 children with ASD constituted the initial research sample, and were randomly assigned into an experiment group and a control group through a lottery process (1:1). Nevertheless, eight (8) children from the control group decided not to participate despite their initial consent. Thus, the final sample consisted of 34 children with an experiment group (EG) (n = 21) (M = 9.57 years, SD = 1.63, 17 males and 4 females) and a control group (CG) (n = 13) (M = 9.69 years, SD = 1.49, 6 males and 7 females). None of the participants had previous learning or practical experience in indoor climbing.

Instrument

In this study, the Visual Attention Therapy Lite accessible application was used, which is the digital attention-assessment tool previously employed in Oriel et al.’s [43] study to evaluate attentional skills in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. The test requires participants to visually scan for a designated target, such as a specific symbol, letter or number, and it automatically records the total time of test completion and number of errors.

The Six Letter Cancellation Test (SLCT) has been widely employed to measure selective attention, offering normative data and psychometric validation. It was first validated by Sarang and Telles [44] in the context of relaxation interventions, further confirming the tool’s reliability in experimental settings. Furthermore, it was also used in the study of Pradhan and Nagendra [45] in written form with pre- and post-cancellation test scores found to be valid and reliable (r = 0.781, p = 0.002).

The digital assessment of attention using cancellation tasks is a well-established method in psychometric and neuropsychological evaluation, with proven validity and reliability. Langner et al. [46] provided a comprehensive environment for administering and analysing cancellation tasks on touchscreen or desktop devices using the Cancellation-Tools platform, supporting the functional equivalence between digital and paper formats while offering extended analytic capabilities. Also, Bouyer et al. [47] demonstrated that computerised versions of cancellation tests do not produce statistically significant differences compared to their paper-based counterparts, thus confirming the validity of digital adaptations.

Furthermore, di Cesare et al. [48] emphasised that cancellation tasks are sensitive tools for capturing developmental changes in attentional structure, thereby supporting their generalisability across age groups. Collectively, the use of Visual Attention Therapy Lite in the present study is methodologically and scientifically justified as a digital equivalent of a validated attention assessment instrument. The device used in our study was an Apple iPad (A16, screen size 11").

Procedure

The duration of the indoor climbing program for the experiment group (EG) was 10 weeks, at a frequency of 3 sessions per week, for 1 hour each session. The 1-hour practice included 10 min of warm-up climbing exercises followed by climbing training of 45 min with elements of climbing games, learning of basic climbing wall techniques and various climbing formations and a 5 min cool-down period. The starting and finishing holds of each route were always clearly distinguishable (either larger in size or prominently marked). Climbing routes were categorised by difficulty levels according to the French grading system of climbing [38] and they were structured either by colour (e.g., a route where only yellow holds and footholds can be used) or by marking holds and footholds of different colours with tape or chalk that the child must follow. The focus was on helping the children make the right decisions regarding their next move following visual cues, with a particular focus on which hold to choose while ignoring all the others, how to grip or step on it, and how to position their body to execute the next move, in this way directing their attention to successfully complete the designated climbing route.

Control group participants (CG) did not participate in the climbing program. Nevertheless, it should be noticed that the delivery of the climbing program was offered to the control group on completion of the postmeasures and the climbing program continued to run after the end of research for all interested individuals with ASD.

Selective attention of all (EG and CG) participants was assessed pre- and post-application of the climbing program, using the digital cancellation test via an iPad application to evaluate pre- and post-cancellation test scores.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis included the use of SPSS 29.00 for research purposes. A non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used to identify statistically significant differences between pre- and post-measurements in each group (EG and CG), whereas a Mann–Whitney test was applied to locate pre- and post-measurement differences between the EG and CG, concerning pre- and post-cancellation test scores of time and mistakes made during testing. Based on Bonferroni corrections (p-value < 0.05 divided by the number of tests – measurements), the significance of the results of all statistical tests was established at p < 0.0125.

Results

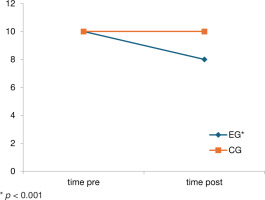

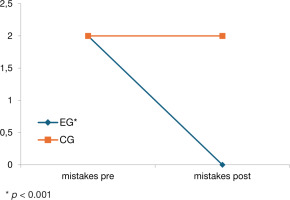

The Wilcoxon non-parametric analysis revealed statistically significant differences between pre- and post-measures only for the EG group on both factors (time and mistakes), with EG participants exhibiting an improved time with fewer mistakes made in the cancellation test following the end of the climbing program. No statistically significant differences were observed between pre- and post-measures of the CG (Table 1, Figures 1, 2).

Table 1

Wilcoxon test results of EG and CG

Table 2

EG and CG differences in pre- and post-measures

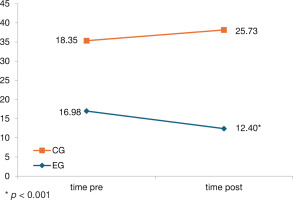

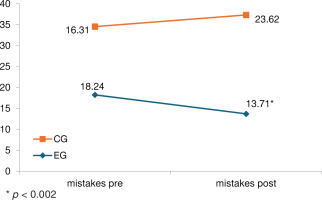

The Mann–Whitney test revealed statistically significant differences between EG and CG for time and mistakes in post-measures of the cancellation test, in favour of the EG participants. No significant differences were noticed in the initial measurements between the two groups (Table 2, Figures 3, 4).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of an indoor climbing program on selective attention of children with ASD, using mobile apps of cancellation test in pre- and post-measures, showing that such improvements in selective attention of children with ASD can be achieved. In particular, the EG of children with ASD displayed improvement on both cancellation test features in post measures with less time and significantly fewer errors to complete the test compared to the pre measurements, whereas no related differences were observed for the CG participants, which is attributed to the absence of any intervention.

The findings are in agreement only with an indoor climbing study contacted by Angelini et al. [41] for children with ADHD, suggesting that climbing requires sustained attention and cognitive engagement, as participants must continuously scan for holds, plan movements, and make real-time decisions while physically executing those movements. Angelini et al. [41] suggest that climbing enhances attentional control by engaging children with ADHD in processes that require them to filter out distractions and focus on a specific goal through visual stimuli, such as the climbing routes structured by colour in our study. Nevertheless, further supportive evidence is needed for ASD populations.

In our study, the visual support provided by climbing appears to help children with ASD to concentrate on key aspects of a task by reducing irrelevant stimuli, training children to focus on what is most important (such as holds in climbing or essential visual cues in learning) to encourage selective attention. Indoor climbing is ideally suited to the preferences of individuals with ASD and activates selective attention in conditions where it functions optimally [6]. Young children with ASD exhibit impaired selective visual attention to social stimuli (faces) and increased attention to non-social stimuli (fractals). It is reasonable to assume that nonsocial objects, such as uniquely shaped climbing holds, also fall into this category.

Climbing is a sport that requires focused attention to advance along the route without making mistakes or falling while avoiding distractions from external factors that could impact performance. This aligns with the cognitive-motor engagement hypothesis as described by Garrido-Palomino et al. [39], which suggests that repeated engagement in climbing tasks requires both cognitive and physical effort that can enhance cognitive function and particularly attention. This hypothesis suggests that climbing requires constant visual scanning, decision-making and motor coordination, leading climbers to develop superior attention skills compared to non-climbers [49, 50]. In a sense, experience in climbing enhances the brain’s ability to process visual and spatial information more efficiently, allowing climbers to identify and react to important cues, such as handholds and footholds, while minimising distractions [49].

The cancellation test is a tool frequently utilised in various studies to assess attention levels in individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD and ADHD [23, 24]. Oriel et al. [43] supported rock climbing as a potentially effective recreational activity for adolescents with ASD that can contribute positively to their physical, psychological and social development. Their study demonstrated that rock climbing can be an inclusive and adaptable activity for individuals with ASD and emphasised the need for further exploration of structured physical activities. However, Oriel et al.’s [43] study yielded no statistically significant results in cancellation test scores in post-measures, compared to our study, probably due to their small sample size, less frequent climbing sessions per week, and lack of visual stimuli during the climbing sessions that could encourage selective attention.

Cohen and Demchak [16] focused on the role of visual cues that provide support towards task independence and improved selective attention in students with ASD, concluding that visual supports are a powerful tool for improving task performance and attention in students with neurodevelopmental disabilities. The findings of this study equally emphasise and support the importance of suitable interventions based on different disabilities and individual needs, highlighting the potential of visual strategies during climbing to promote performance and selective attention for children with ASD.

Images, symbols, colours, or diagrams to detect handholds and footholds across the climbing route draw the visual attention of children with ASD into a purposeful and goal-directed task. Climbing demands focus on visual cues for navigating the wall, promotes visual and cognitive engagement through targeted tasks and helps children with ASD to develop and improve their attention control, which is crucial for success in education and daily life [18, 39].

Conclusions

Overall, it seems that the findings support that a 10-week indoor climbing program for individuals with ASD with a duration and frequency of climbing sessions per week as in this study, may enhance their level of selective attention in environments rich in visual stimuli that align with their expectations. Indoor climbing along with visual stimuli can provide cognitive benefits that children with ASD gain through visual cues, making such intervention effective in promoting selective attention and climbing performance. In educational settings, an indoor climbing wall is easy to construct with holds and routes at low heights, padded surfaces or gradual inclines that minimise injury risks and create a sense of achievement while offering a non-verbal means of expression and accomplishment. Including climbing opportunities in the daily school schedule can help children with ASD to regulate sensory input, promote concentration and encourage problem-solving and planning through goal-directed activities and visual cues.

Therefore, indoor climbing appears to be an ideal physical activity for individuals with ASD. Future research could investigate whether increased selective attention is associated with, for example, faster completion of climbing routes in indoor settings.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include its small sample size, large age differences among participants and the lack of gender-based statistical analysis; thus, future studies could address these issues. Future studies with larger samples could also focus on determining the optimal duration and frequency of different types (free, traverse, top rope) of climbing sessions accompanied with visual supports to promote selective attention and other cognitive functions such as memory, decision-making and learning in children with ASD and other neurodevelopmental conditions.